Simon Bening and the Enriquez de Ribera Prayerbook Miniatures

Simon Bening (1483-1561)

, Flanders, probably Bruges, c. 1520s-early 1530s

Simon Bening (1483-1561)

Description

Three dramatic miniatures painted by Simon Bening (1483–1561), one of the greatest and most famous Netherlandish manuscript illuminators. Newly discovered and unstudied, the present miniatures depict vivid scenes from the Passion of Christ and the Last Judgment from the Enríquez de Ribera Prayerbook. They showcase Bening’s exceptional talent as an illuminator: his flair for using natural light, haunting poetic landscapes, devotional pathos, narrative use of color, and especially his delicate touches of paint on small surfaces.

These three miniatures can now be added to a group of thirteen other miniatures from this Prayerbook, currently dispersed across public and private collections including the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Morgan Library and Museum, the Musée du Louvre, and the Saint Louis Museum of Art. Their discovery the presents the unique opportunity to reexamine the Enríquez de Ribera Prayerbook. Exciting new research has led to our new understanding of their origin.

To understand the originality of Bening’s paintings and their complexity, divided into multiple panels with numerous speech banderoles and sometimes accompanied by headings or titles, it is essential to view them as illustrations to the text they accompanied. We have been able to arrange the extant leaves and cuttings from the Enríquez de Ribera Prayerbook in their correct order in the parent manuscript and to show how each functioned as a link between the narrative of the Passion from Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ and the personal devotion the accompanying prayers encouraged. We have added an alternative caption to each miniature taken from the words of the prayer the viewer recited while gazing at the picture and thus evoking the meditation the prayer triggered.

The three new miniatures discussed here come from diff erent sections of the Life of Christ. Programmatically, they and their sister leaves fi t best in the works for which Bening was responsible in the late 1520s to c. 1530, especially the Stein Quadriptych and the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg, both dated by circumstantial evidence c. 1525–1530. Recent research by Lynn Ransom on the Stein Quadriptych, now arranged on four panels of sixteen scenes each, suggests that its miniatures were never intended to be presented in this form but instead once illustrated a codex of either a Life of Christ or prayers related to the Life of Christ. The forty-two miniatures of the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg accompany meditations or prayers in German on the Life and Passion of Christ arranged in roughly chronological order and copied from a Prayerbook printed in Augsburg in 1521. Not unrelated is the Chester Beatty Rosarium (Dublin, Chester Beatty Library, W099), although dated later to c. 1540–1545 on circumstantial evidence, in that it too included pictures meant to enhance the rosary devotion in the prayers of the accompanying text. Stylistically, the three new miniatures and their sister leaves also relate most closely to these works, as we shall see.

a. Suffer me not

Betrayal of Christ, Christ Confounding Soldiers, Arrest of Christ and Christ Healing Malchus

These four panels are arranged in a quadriptych to depict the Betrayal of Christ by Judas and the episodes that directly follow, all in nocturnal settings, Christ Confounding the Soldiers, then his Arrest, and finally Christ Healing Malchus. Bening is well known for his skillful night-time compositions that show flaming braziers and trailing sparks set against shadowy clouds as seen here. Golden highlights throughout these scenes – on the modeling of the garments, the haloes, the glowing lantern, and the banderole – cast a warm hue over the entire miniature, carefully framed with double gold lines in the same tonality. Bening captures the agony and pathos of each moment by focusing in on the episodes, cutting off parts of the principal actors at the edges of the frame, so that they merge into the viewer’s space. Through careful attention to details of costume and an eff ective use of primary and secondary colors, he guides the viewer through the detailed narrative: Peter reappears in blue and the soldier in red, Judas is dressed in green and yellow, and Malchus in yellow and green. Painted green and yellow, Malchus and Judas match the colors of the Ribera coat of arms seen in the sister leaves, projecting the identity of the viewer into the narrative of the Passion. These are characteristics of Bening’s style also found in the Stein Quadriptych and the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg, which show an evolution from his earlier works such as the Imhof Prayerbook of 1511, where the night scenes and the palette are less nuanced and closer in style to that of the previous generation.

In the Betrayal of Christ, Judas’s coin purse stands out as an unusual iconographic detail, and it reinforces his role as betrayer. As the single spot of red in the first panel, it also guides the viewer’s eye to areas of red in the three following panels. Furthermore, it provides a visual cue for the narrative, as it relates back to an earlier leaf in the manuscript, where Judas holds a red coin purse behind his back at the Last Supper (sister leaf 3). The next panel, Christ Confounding the Soldiers, shows the moment that Christ acknowledges his identity to the Roman legionaries, an act only described in the Gospel of John (18:3-6). This scene is rarely depicted, but it is found in another Flemish Book of Hours (Morgan Library, MS M.696).

The third panel with the Arrest of Christ includes a banderole with text from Matthew 26:55, “TAMQUA(M) AD LATRONE[M EX]ISTIS CU[M] GLADIIS ET FVSTIBVS” (You come as against a robber with swords and clubs). Bening’s use of a pattern is clearly discernable in the figures of Peter and Malchus, a pattern he also used in a miniature in the Imhof Prayerbook (Private Collection, f. 81v). The fourth panel with Christ Healing Malchus shows Malchus a third time, accentuating his role in the Passion scenes, and compares with a miniature in the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg (Getty Museum, MS Ludwig IX 19, f. 102v). Christ, dressed in pale blue-green, the only tertiary color in the composition, stands out as the single serene figure among the participants throughout the four narratives.

The episodes shown in this leaf and the text in the banderole are discussed in Book II, chapter 59, of Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ. The miniature would have served as a prompt to devotion while reciting this chapter’s prayer at First Compline in the evening after dinner, which corresponds with the time of day the Arrest is presumed to have occurred. The prayer focuses on the agony of Christ (“thou didst sweat blood,” Luke 22:44), who suffered “by the kiss of Judas to be handed over to the wicked” (Matthew 25:50), and “to be led bound to Annas” (John 18:12). The devout continues to pray, “Suffer me not to be given over into cruel hands” thus using the episodes from the Passion to “sever the chains of mine evil conscience.” Said at night, while viewing night-time depictions of the events, the prayer gained efficacy: “Suffer me not.”

b. Make me a Joseph

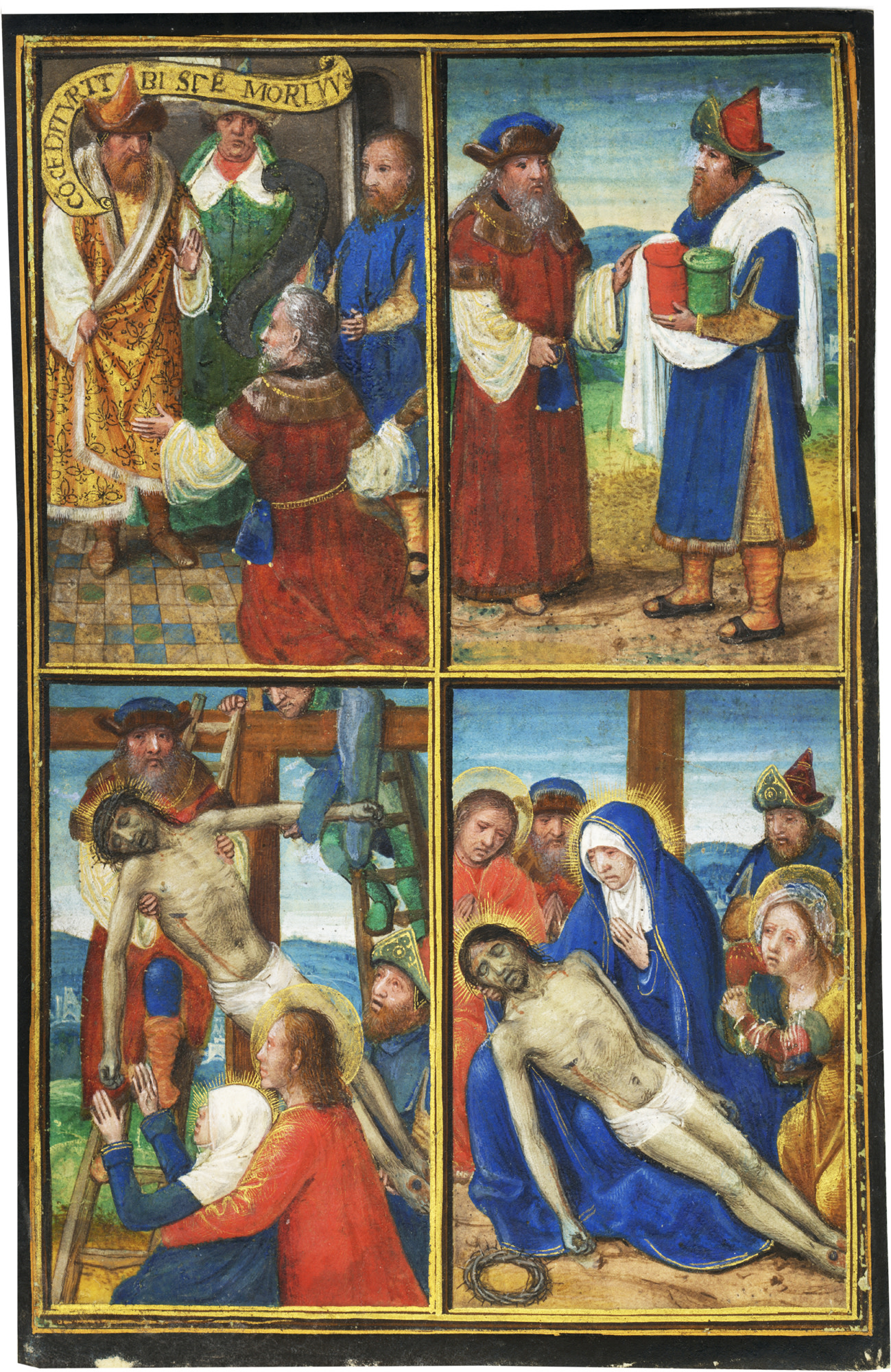

Joseph of Arimathea with Pontius Pilate, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, Deposition, and Lamentation

Arranged in a quadriptych, four scenes focus on post-Passion episodes. The fi rst panel shows Joseph of Arimathea kneeling in front of Pilate to ask for the body of Christ with Nicodemus standing next to Joseph on the far right. Banderoles indicate speech between the fi gures. While the scroll referring to Joseph has been scraped, it probably contained a request for the body of Christ; Pilate clearly answers “CO(N)CEDITUR TIBI S(t?) E MORTUUS” (the body will be granted to you); there is no direct speech in the Gospel accounts. The second panel on the upper right again depicts Nicodemus and Joseph, clearly recognizable by their elaborate robes and exotic hats, on their way to Calvary bathed in a warm afternoon light. Nicodemus carries myrrh, aloe, and the white linen, with which to treat and wrap the body. Nicodemus’s role is related only in the Gospel of John (19:39-40). Joseph reaches out with his left hand to touch (or give?) the linen in Nicodemus’s arms.

The unusual scene of Joseph of Arimathea can occasionally be found in other illuminations of the Bening milieu, for example in the Grimani Breviary (Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, MS lat. 99 [2138], ff. 138v–139) by the Master of James IV of Scotland. Bening also depicts the scene in a full-page miniature in the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg (Getty Museum, MS Ludwig IX 19, f. 311v), but the figures are arranged differently, and the scene occurs outdoors in front of a very impressive cityscape instead of in a landscape. The encounter of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus on their way to Calvary in the second panel has no iconographic parallel and appears to be unique to Bening’s oeuvre.

The two lower panels depicting the Deposition from the Cross and the Lamentation also include Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, although they play less prominent roles. In the Deposition the two men lower the body of Christ from the Cross, while John holds the swooning Mary, arms upraised toward the body of her dead Son. In the Lamentation, they are spectators, looking on from behind the central group on the left and right of the cross. For both scenes, Bening relied on patterns he also used elsewhere, especially, but not exclusively, in the late 1520s, for instance, in the Stein Quadriptych, the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg, and the Prayerbook for Joanna of Ghistelles (dated c. 1516; British Library, Egerton MS 2125, f. 154v). The group featuring the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of her son with her right hand, while she gestures in grief with her left, and Mary Magdalene, wringing her hands in agony, also recalls Roger van der Weyden’s famous panel painting the Descent from the Cross (Museo del Prado, P002825), executed between 1435 and 1440.

The chief subject of the miniature, Joseph of Arimathea, is the focus of the narrative in chapter 65 of Book II of Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ and its accompanying prayer. The prayer is to be said at Second Vespers in the late afternoon, when the Lamentation took place – as depicted in the warm afternoon sunlight that bathes three of these episodes. In the prayer, the supplicant beseeches Christ: “make me a Joseph increasing in virtue from day to day” for “thou didst suffer Joseph of Arimathea to take thee down from the cross and receive thee within his arms .…” Like Joseph, the believer offers a “sachet of myrrh within my arms with love.”

c. Oh Mary help me

Souls Entering Heaven, Christ Appearing to His Mother, Souls of the Saved Brought to Heaven, and Last Judgment

Four panels on this leaf comprise two cuttings mounted together on the same wood support; the top two panels are still joined together, as are the lower two panels. Initially, I believed that they were perhaps not from the same leaf. However, as we shall see, an understanding of the text of the prayer suggests otherwise. Although they were cut apart at some point in their history, they are now mounted together as they originally appeared.

The fi rst panel with Souls Entering Heaven shows four fi gures emerging from their graves and entering the gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem, here rendered in detail with tall Gothic spires and a vaulted apse with pointed arches at center. The iconography is comparable to a panel by Dieric Bouts with the Ascension of the Elect of c. 1450–1468 (Fig. 20; Lille, Palais de Beaux-Arts, inv. no. P 820), a comparison suggested by Testa.

On the upper right, Christ Appearing to his Mother (the central subject of the prayer) depicts Christ surrounded by a glowing aura when the first greets his mother after the Resurrection. Sitting next to her bed, Mary turns her gaze away from the Prayerbook in her lap and raises her hands to witness her son in triumph. Delicately painted in liquid gold inside Christ’s mandorla are small faces, most likely representing the souls of the saved. This episode is not in the Bible, but it does appear in Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ.

The closest comparison among Bening’s miniatures is to the Stein Quadriptych, where Christ is shown in pinkish red, the souls of the saved emerging in golden hues in the aureole behind him (Walters Art Museum, W.442.D, 58r).

For the third panel with Souls of the Saved Brought to Heaven (Fig. 23), Bening again relies on a pattern, in this case one that he probably inherited from his father. The two figures with souls on the backs of angels can be recognized in a miniature by the Master of the First Prayerbook of Maximilian in the Hours of Queen Isabella the Catholic (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1963.256.24.b, f. 24v) and in the Grimani Breviary (Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, MS lat. I, f. 469). The Master of the First Prayerbook of Maximilian has now been identified as Alexander Bening.

Finally, the fourth panel depicting the Last Judgment shows Christ seated in heaven with four angels and the twelve apostles beside him, while below appear the souls of the saved on the left and the tormented souls of the damned on the right. Stylistically this miniature can be related to Bening’s Last Judgment on a leaf from the Prayerbook of Albrecht of Brandenburg in Cambridge (Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 294d). The folds of Christ’s robes are perhaps from a pattern that appears in the Last Judgment Bening painted in the Van Damme Hours, dated to 1531 (Morgan Library, MS M.451, f. 91v).

The prayer accompanying Ludolph of Saxony’s description of the episode of Christ appearing to his mother focuses not on the narrative moment but on Mary’s help to the devout “on the last day” to “escape the sentence of eternal damnation and arrive happily with all the elect of God to joys eternal.” It opens “O Mary, Mother of God and virgin full of grace ... the joy of knowing the Lord Jesus glorifi ed arose from the dead on the third day, be the consolation of my soul.”41 The prayer thus ties the narrative moment to salvation, as the four scenes together illustrate.