The Lubbock Hours (Use of Sarum), with a Missal fragment

, Bruges, c. 1390-1400, and England, c. 1400

The Lubbock Hours (Use of Sarum), with a Missal fragment

Description

This richly illuminated Book of Hours survives as a compelling example of pre-Eyckian book illumination from a subgroup called the Pink Canopies Group, of whose work only eight codices survive, including four in public collections. One of the finest of the group, the present manuscript has been considered “lost” since 1937. The bold expressive figures set beneath pink architectural canopies are rendered with the subtle plasticity of Pre-Eyckian realism and are typically set against highly decorative backgrounds. Pre-Eyckian paintings are so rare that only thirty – all in museum collections – have been recently traced from the decade or so before Jan van Eyck (1395-1441) in Bruges. Few such paintings are ever available on the art market. Manuscript illumination of the period greatly enhances the scope of appreciation of Pre-Eyckian art, and the paintings surviving in manuscripts like the present one are often in near-perfect states of preservation.

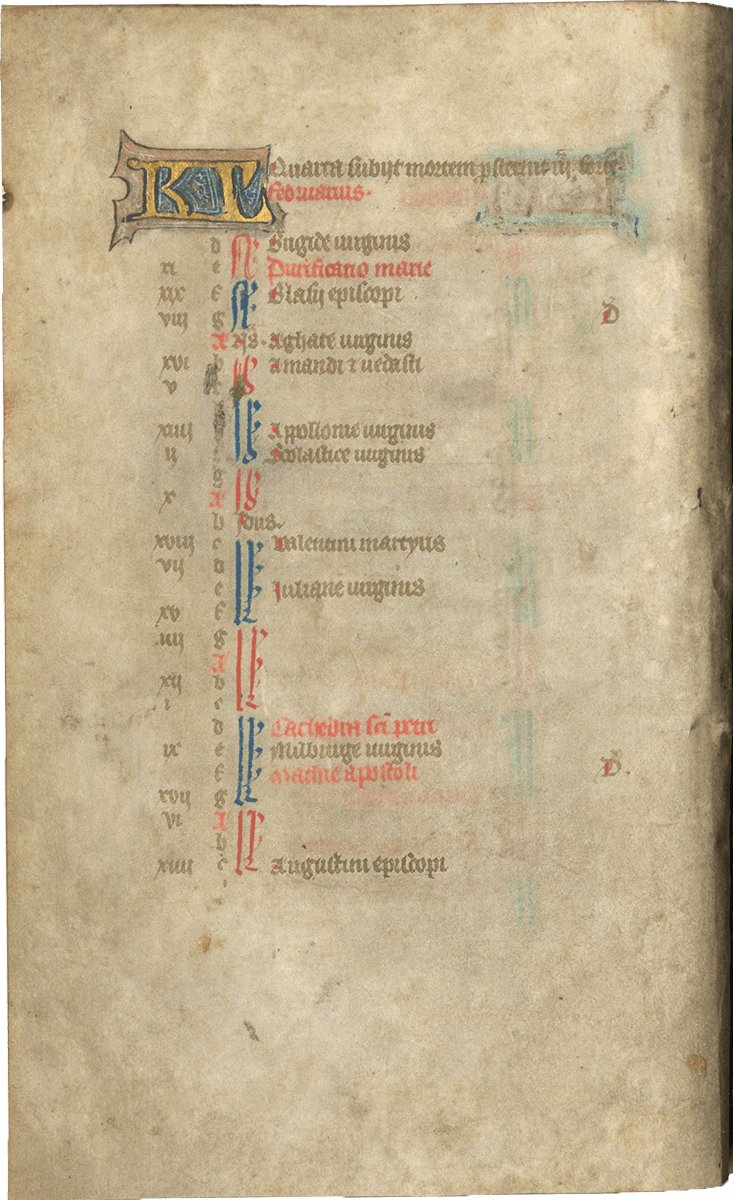

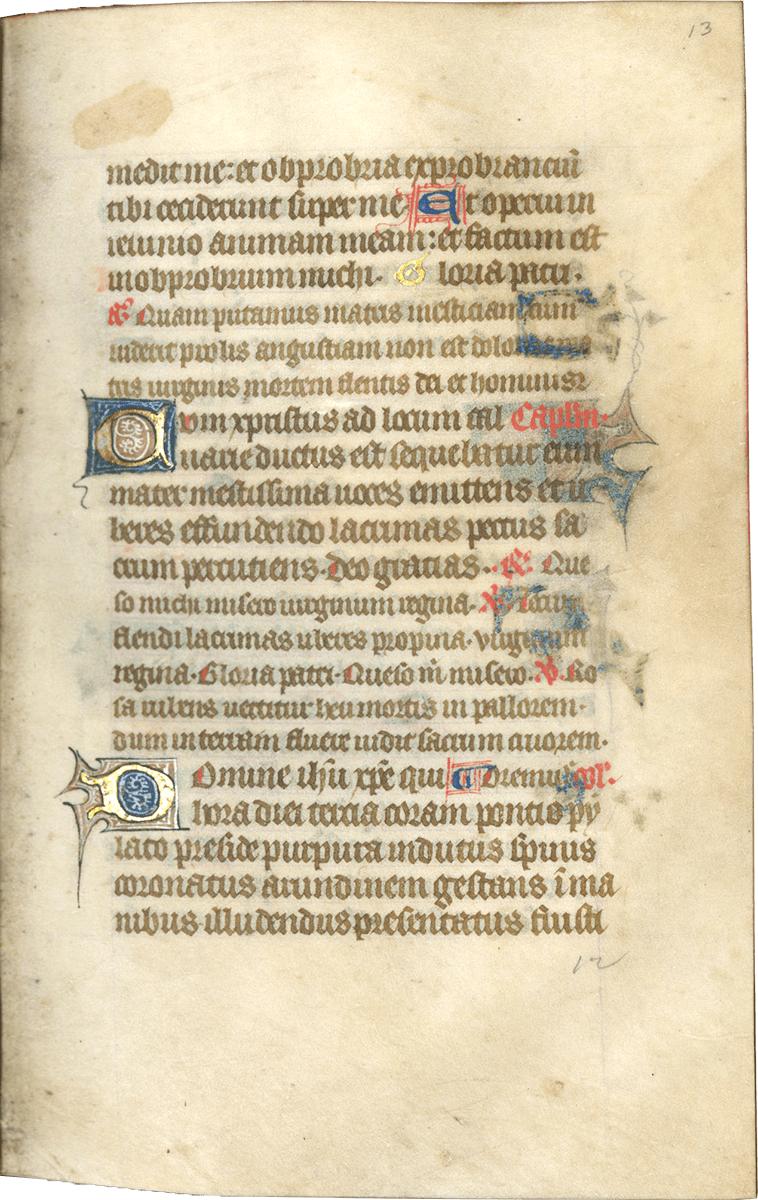

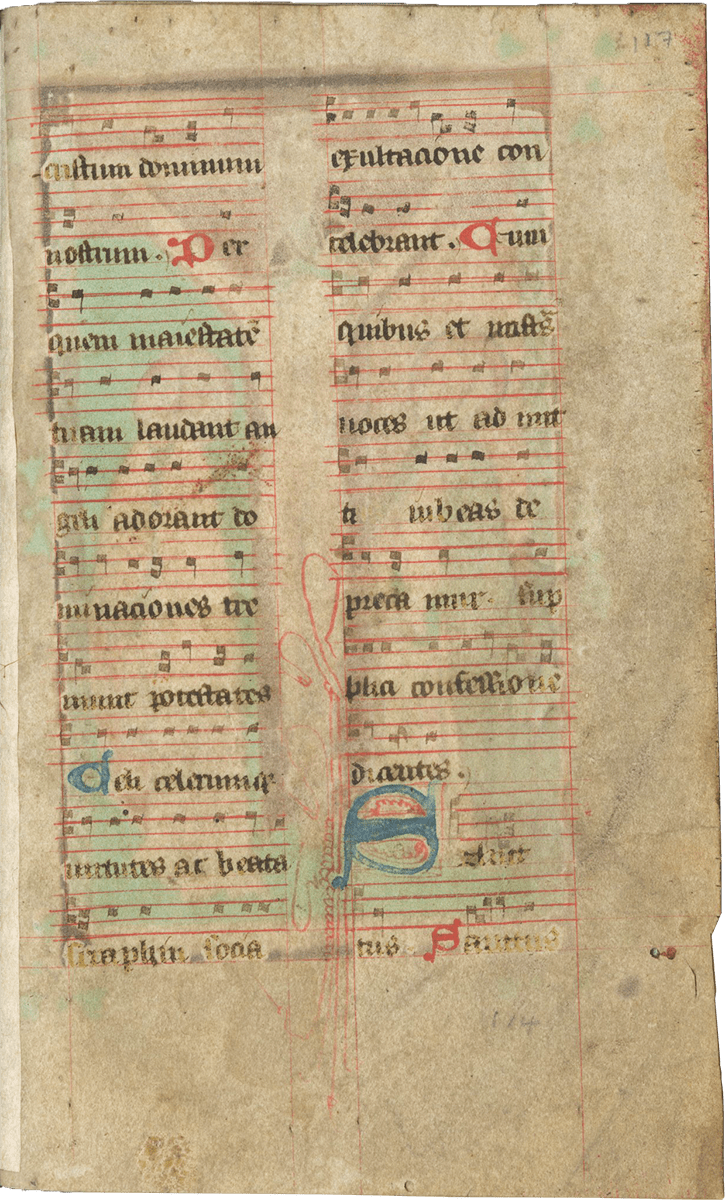

ii (modern parchment) + 124 + ii (modern parchment) folios, modern foliation in pencil, probably missing two leaves with miniatures of Saint John the Evangelist and of Saints George and Edmund transposed, one or more leaves with the end of the Commendation of Souls and with the beginning and the ending of the Missal section, else complete (collation: i6 ii8 [+1; f. 7, inserted as a singleton] iii4 [+ 2 singletons, ff. 19 and 21, added after 3 and 4] iv4 [beginning, f. 22: + 4 singletons, ff. 23, 25, 27, 29, inserted after 1, 2, 3, and 4] v6 [+ 5, singletons, ff. 31, 33, 36, 38, 40, inserted after 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6] vi2[+ 2 singletons ff. 42 and 44, inserted after 1 and 2] vii8 [beginning f. 45] viii8 ix8 [+1, f. 68, singleton added after 7] x8 xi8 [+2, f. 80, and 87, singletons added after 2, and 8] xii8 xiii8 [+1, f. 98, singleton added after 2] xiv8 xv4 [structure uncertain, ending imperfectly] xvi8, ff. 1-112v written in brown ink in a fine Gothic bookhand on 22 lines, ruled in pale brown ink (written space: 113 x 70 mm), rubrics in red, line fillers in red and blue, one-line initials in gold with purple pen decoration and in blue with red pen decoration, two- to three-line initials in gold on grounds of blue and rose with white ornamentation and with ivy-leaf extensions into the margins, ten five-line foliate initials on gold grounds with leafy extensions forming partial or full borders in the margins, EIGHTEEN FULL-PAGE MINIATURES, ff. 113-124 (added English section), written in two columns of 30 lines (written space: 125 x 75 mm), with music in square notation on four-line red staves, one-line plain initials alternating in red and blue, two- to three-line blue initials with red pen decoration, sometimes containing the profiles of human faces, four-line foliate initial with a full border at the beginning of Easter, five-line foliate initial with a full border at the opening of the Canon of the Mass, ONE FULL-PAGE MINIATURE, some miniatures rubbed and some marginal decoration cropped at the edges, but generally in sound and good condition. Bound in a twentieth-century blue velvet binding, quires tipped-in, spine raised on six raised bands, in excellent condition. Dimensions 170 x 115 mm.

Provenance

1. Made in Bruges for export to England. The presence of a miniature of St. Edmund (of Bury St Edmunds) and a calendar entry for St. Fremund both point to an East Anglian destination for this manuscript. Fremund was a relative of Edmund and both were martyred by the same band of Vikings, for which reason John Lydgate paired them in his Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund. A related manuscript in Cambridge University Library (see Illustration, below) also has early East Anglian connections and may be the work of the same artist.

2. An unidentified fifteenth-century English owner has inscribed in the calendar page for September, in which the feast of the “Exaltatio” of the Holy Cross (14 September) is in red, “Encq’[?] on the morn affore holle ruddaye [i.e. Holy Rood Day, 14 September] / et sant Regaud evyne [i.e. and St. Rigaud’s even(ing)?]” (f. 5, lower margin).

3. This manuscript was still in England at the time of the Reformation, perhaps in recusant hands. This possibility is suggested by the curious treatment of this book’s contents: references to the pope have been erased from the calendar and the Canon of the Mass (f. 115), indicating that the book was in England and subject to Henry VIII’s decree, and yet the miniature of Becket, the prayers addressed to him, and his entries in the calendar all remain intact.

4. Offered by J. J. Leighton in 1915; item 151 in his Catalogue of Manuscripts, Mostly Illuminated, Many in Fine Bindings, London, 1915 (with plates on pp. 166-167).

5. Belonged to Lt.-Col. William Edward Moss (1875-1953) of the Manor House, Sonning-on-Thames. Sold in his sale at Sotheby’s, 5 March 1937 (lot 834).

6. Bought in the 1937 sale by Maggs for Major Sir Alan Lubbock (1897-1990); Lubbock’s armorial bookplate and pencil inscription with two comparanda, “Westminster Abbey Lib. f.47 (Liber Regalis) / & Trin. Coll. (Cant) MS.B.II.7 f.20,” on the back pastedown.

7. Private European collection.

Text

ff. 1-6v, Calendar with entries including Julian (4 March), Walric (1 April), Peter Martyr (29 April);

ff. 8-18v, [f. 7, blank; f. 7v, miniature], Long Hours of the Sorrow of the Virgin, with a rubric detailing an indulgence of forty years granted by Pope John XXII, Hec sunt hore de dolore beate Marie virginis quas composuit dominus Iohannes papa vicesimus secundus ...;

ff. 20-43, [f. 19, blank; f. 19v, miniature], Memoria to the Trinity (f. 20), the Holy Face (f. 22), Saint Thomas Becket (f. 24), the Arma Christi (f. 26), Saint Edmund (f. 26), Saint George (f. 30), and Saint Anne (f. 32), a prayer on the names of the Virgin Mary (f. 32v), and memoria to Saint Mary Magdalene (f. 34), Saint John the Evangelist (f. 35), Saint John the Baptist (f. 37), Saint Christopher (f. 39), Saint Catherine (f. 41), and Saint Margaret (43);

ff. 45- , [ff. 43v-44, blank; f. 44v, miniature], Hours of the Virgin, with Matins (f. 41), Lauds (f. 44), Prime (f. 52v), Terce (f. 54v), Sext (f. 56), None (f. 57v), Vespers (f. 58v), and Compline (f. 60), with memoria (ff. 49-52v) after Lauds to the Virgin, the Holy Spirit, the Trinity, the Cross, Michael, John the Baptist, Peter and Paul, Andrew, Stephen, Laurence, Thomas Becket, Nicholas, Mary Magdalene, Catherine, Margaret, All Saints, for Peace, and the Cross, with the Short Hours of the Cross intermixed;

ff. 69-72v, [ff. 67v-68, blank; f. 68v, miniature], Salve regina;

ff. 72v-73v, “O intemerata” (with masculine forms);

ff. 73v-75v, “Obsecro te” (with masculine forms);

ff. 75v-77v, Seven Joys of the Virgin, with a rubric detailing an indulgence of one hundred days granted by Pope Clement (with masculine forms);

ff. 77v-79, “Ave mundi spes Maria”;

ff. 81-83 [ff. 79-80, blank, f. 80v, miniature], Devotion to the Crucifixion in the form of prayers to an image of the Crucifix, the wood of the Cross, Christ’s head and the Crown of Thorns, each of Christ’s five wounds, and the Virgin Mary, followed by versicles and a collect;

ff. 83-84, Prayer of Bede on the Seven Last Words;

ff. 84-86, Prayers, including “Precor te piissime domine Ihesu Christe,” “Ave domine Ihesu Christe, verbum patris,” “Ave verum corpus domini nostri Ihesu Christi,” “Anima Christi sanctifica me, corpus Christi salva me,” “Ave caro Cristi [sic] cara, immolata crucis ara,” and “Domine Ihesu Christe qui hanc sacratissimam carnem tuam,” the last of these with a rubric detailing an indulgence of two thousand years granted by Pope Boniface;

ff. 88-93 [ff. 86v-87, blank; f. 87v, miniature], Seven Penitential Psalms;

ff. 93v- 95, Litany;

ff. 95v-97v, Added prayers including “Pietate tua quesumus domine nostrorum solve vincula delictorum” and “Omnipotens et misericord deus clem[entiam] tuam supliciter deprecor”;

ff. 99-112v, [f. 98, blank with later notes; f. 98v, miniature], Office of the Dead;

ff. 113-116v, Commendation of Souls, ending imperfectly at Psalm 118:126 (at “... dissipaverunt leg[em]”);

ff. 116-124v, Added fragment of an English noted Missal, with the end of musical settings of the Sanctus, the Canon of the Mass, the mass for Easter day, and part of the mass for the day after Easter, ending imperfectly in the communion “Surrext dominus.”

Illustration

The subjects of the nineteen full-page miniatures are as follows:

f. 7v, Pietà, with the Virgin seated in front of the Cross with the naked body of Christ lying across her lap;

f. 19v, Throne of Mercy, with God enthroned, holding the crucified Christ in front of him;

f. 21v, Sudarium, with two angels holding aloft the veil of Veronica, imprinted with the face of Christ;

f. 23v, Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, with Becket kneeling in prayer before an altar with an open book (its words and notes legible) and a chalice, his mitre knocked on the ground, as the knight FitzUrse (identifiable by the two bears on his shield) strikes Thomas on the head with a spear and a second knight prepares to strike with a sword;

f. 25v, Christ as Man of Sorrows, shown half-length, surrounded by the Instruments of the Passion;

f. 27v, Saint George on horseback slaying a dragon;

f. 29v, Saint Edmund tied to a pillar and impaled by arrows, with a repeated pattern in the background including the letters “vro” (perhaps a mistake for “oro,” meaning “I pray”);

f. 31v, Virgin and Child on the lap of Saint Anne;

f. 33v, Saint Mary Magdalene holding her ointment-jar and a palm of martyrdom, with repeated pattern in the background incorporating her initial “m”;

f. 36v, Saint John the Baptist holding a very small Agnus Dei on a book;

f. 38v, Saint Christopher carrying the Christ Child across a river;

f. 40v, Saint Catherine holding a sword and a wheel, with the hem of her cloak inscribed “Gloria in excelsis deo / omnipotens / mater dei / S. Katerina”;

f. 42v, Saint Margaret emerging unscathed from the belly of a dragon;

f. 44v, Annunciation, with a kneeling Gabriel holding a scroll inscribed “Ave gratia plena dominus tecum” before the standing Virgin;

f. 68v, Seated Virgin holding the Infant Christ, her robe embroidered repeatedly with the name of Jesus (“ihe [sic]”);

f. 80v, Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John;

f. 87v, Last Judgment, with Christ seated on a rainbow and displaying his wounds with a sword on either side of his mouth and with three souls emerging from graves below;

f. 98v, Funeral Service, with two lighted tapers in front of a bier covered with a pall embroidered repeatedly with the formulation “:ali:” and with two priests, one holding an open book inscribed with music and the names of the Evangelists: “Mateu[m] / S. Lucam] / [Ioh]anem / [Mar]cam [sic]”;

f. 117v, Crucifixion, with Christ and the Cross against a gold background and with Mary and Saint John standing on daisy-strewn grass against backgrounds of pink and green, respectively, each patterned in gold.

The first eighteen of these nineteen miniatures were executed perhaps in Bruges or perhaps in England by an illuminator belong to the so-called Pink Canopies (or Rose Baldachins) group (they are all on inserted sheets). This group was first studied in detail by Maurits Smeyers in Vlaamse Miniaturen voor Van Eyck (ca. 1380-ca. 1420): Catalogus, Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts 6 (Leuven, 1993), pp. 4-12, and briefly summarized by him in English in Flemish Miniatures from the 8th to the mid-16th Century (Turnhout, 1999), pp. 203-204. More recently, the group has been discussed in some detail by Sandra Hindman et al. in Illuminations in the Robert Lehman Collection (New York, 1997), pp. 53-60. Recent examination of the present manuscript by two specialists of English manuscript illumination Lucy Freeman Sandler and Kathryn Smith suggest that the entire manuscript was written in Britain. Could imported miniatures have been inserted or might the Pink Canopies illuminators be English or of English origin – part of the International Style of c. 1400 that included Rhenish, English, and Flemish artists?

Apart from the present manuscript (known to Smeyers and Hindman only from the 1937 auction catalogue), the group consists of four codices and a single leaf in institutional collections, and three more codices that have passed through the London market in the past century:

1. London, British Library, Sloane MS 2683

2. Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.6.2

3. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Canon. liturg. 251

4. Montreal, University of Quebec, Special Collections, MS 2 (very recently discovered)

5. New York, Metropolitan Museum, Lehman Collection no.1975.1.2469 (single leaf)

6. Sotheby’s, 1 December 1987, lot 52

7. Sotheby’s, 7 December 2010, lot 4

8. Christie’s, 16 July 2014, lot 9

This richly illuminated Book of Hours survives as a very fine example of Pre-Eyckian book illumination from a subgroup called the Pink Canopies Group, of whose work only eight codices survive. One of the finest of the group, the present manuscript has been considered “lost” since 1937. The bold expressive figures set beneath pink architectural canopies are rendered with the subtle plasticity of Pre-Eyckian realism and are typically set against highly decorative backgrounds. Other features include the gold and black patterned backgrounds; repetitive patterns used in floors, and other features; expressive figures, their flesh often modelled with a greenish under-layer; and luxuriantly folded draperies. The artist of the present manuscript is notable for painting especially voluminous draperies and for his scalloped halos. His miniatures provide a remarkable contrast between flat, two-dimensional floors and backgrounds and wonderfully modelled, fleshy, voluminous, plastic figures with a high degree of individuality and expressive faces.

Pre-Eyckian realism can be seen in many little details: in the Pietà, the Virgin’s raised little finger, the way in which Christ’s hair hangs vertically and in which one limp leg lies under the other; on the veil of Veronica, the subtle modelling of the face of Christ in pale green, white, and pink; in the martyrdom of Saint Edmund, the deliberately brutish face of one of the archers; and the tender gaze of Saint Anne looking at her daughter and grandson, to name just a few. Pre-Eyckian paintings are so rare that only thirty – all in museum collections –have been recently traced from the decade or so before Jan van Eyck (1395-1441) in Bruges. Few such paintings are ever available on the art market. Manuscript illumination of the period greatly enhances the scope of appreciation of pre-Eyckian art, and the paintings surviving in manuscripts like the present one are often in near-perfect states of preservation.

A particularly interesting miniature and fortunate survival is that depicting the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket. Not only is the miniature full of biographical detail (eye-witness accounts relate, for example, the way in which his miter was knocked from his head to the floor), but miniatures and texts relating to Becket were usually defaced, in accordance with a decree of Henry VIII in 1538 (see Eamon Duffy, Marking the Hours, New Haven, 2006, plate 106, which shows the equivalent miniature, possibly by the same illuminator, but seriously defaced, and plates 14, 15, 53, and 54, for related manuscripts).

The added English full-page miniature is equally expressive, especially in John’s furrowed brow and in the very unusual way in which he and the Virgin each lace their fingers together. The tall, elongated figures have something in common with those in a Crucifixion in Oxford, Oriel College, MS 75 (see Kathleen Scott, Later Gothic Manuscripts 1390-1490, London, 1996, ill. 159), and John interlaces his fingers in a somewhat later Crucifixion in London, Guildhall, Muniment Room MS 515 (see Scott, 1996, ill. 190 and a color plate in Richard Marks and Paul Williamson, Gothic: Art for England 1400-1547, exhibition catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2003, p. 417); the latter appears to have been illuminated in East Anglia, perhaps in Norwich.

The fabrication of the present manuscript for an English owner, its presence in England from the time of its origin, and the added English text and illumination signal the close relationship between Bruges and England in part stimulated by the wool trade. The strands of influence between English, Flemish, French, and German painters, all practicing the Gothic International Style that was part of pre-Eyckian realism, merit further study.

Literature

Smeyers, Maurits, ed. Naer natueren ghelike: Vlaamse miniaturen voor Van Eyck (ca. 1350-ca.1420), Leuven, 1993, pp. 90-91 (with a full-page color plate of the Becket miniature).

Vertongen, Susie. “Herman Scheerre, the Beaufort Master and the Flemish Miniature Painting: A Reopened Debate,” in Flanders in a European Perspective: Manuscript Painting around 1400 in Flanders and Abroad (Proceedings of the International Colloquium, Leuven, 7-10 September 1993), 1995, pp. 251-265 (at p. 255 and fig. 2 a full-page plate of the Saint Catherine miniature, wrongly described as f. 40v).

Hindman, Sandra, et al. in Illuminations in the Robert Lehman Collection (New York, 1997), pp. 53-60.

Smeyers, Maurits. Flemish Miniatures from the 8th to the mid-16th Century (Turnhout, 1999), pp. 203-204.