Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, with interpolations of Gui de Mori, Roman de la Rose

, Southern Netherlands, Tournai, c. 1390

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, with interpolations of Gui de Mori, Roman de la Rose

Description

“THE JEANSON ROSE”

A splendid, grand copy of a seminal text of French literature, with rare interpolations by Gui de Mori, illuminated by Jean Semont. Jean Semont is the first illuminator documented by name in the artistic center that produced some of the most important early Flemish panel paintings by Robert Campin and Roger van der Weyden. This pivotal work fits neatly into the artist’s career, and compares closely with his securely documented manuscript, the Missal for Jean Olivier (Valenciennes, BM, MS 118). Exceptionally luxurious ivy-leaf and burnished gold initials and border decoration ornament nearly every page, complementing the three fine illuminations all attributed to the master illuminator. The frontispiece is unique in cycles of Rose illumination. Jean Semont’s works are crucial to understanding the advent of Flemish realism in Tournai before Jan van Eyck, and the Jeanson Rose plays a notable role in that story.

182 folios, on parchment (collation i-ii8 iii8 [-2] iv-xix8 xx9 [1, a singleton] xxi-xxii8 xxxiii6) 1-2837(lacking ii) 4-198 209(i a singleton), 21-228, 236), catchwords an entire line written in a small cursive hand in the inner lower margin of final versos, two columns of 36 lines written in a Gothic bookhand in black or brown ink between 37 horizontals, top and bottom ruled across the margin, and four verticals ruled the height of the page, pairs of verticals the height of the text separating the initial letter of each line, all ruled in plummet, (justification 226 x 68-14-68 mm.), rubrics in red, every page illuminated with two-line initials alternately dark pink or blue on grounds of burnished gold with trefoil leaves in the infills and delicate ivy-leaf sprays extending into the margins, opening folio with introductory miniature and a full-page border with drollery figures in the bas-de-page and margins, the other texts opening with two further miniatures, one with a full-page border (opening folio slightly darkened and thumbed at the outer edge, tiny pigment losses from the bed-hangings in the miniature, smudging of a few initials, the Trinity miniature on f.153 worn, presumably by kissing). Eighteenth-century French mottled calf binding gilt (splits at head and foot of upper joint, extremities scuffed). Dimensions 320 x 205 mm.

Provenance

1. The majority of the extant manuscripts of the Roman de la Rose were made in northern France, many of them in Paris. This manuscript, on the other hand, was produced in Tournai: the Picard features of the text and the style of illumination are typical of the manuscripts produced in this region at the turn of the century.

2. There are brief annotations and nota signs written in French in a 15th-century hand in some margins, including names identifying the marginal figures of the opening folio. A title in French, in manuscript, within an 17th-century engraved surround is pasted on to a front endleaf.

3. Sir Jacob Astley Bart, of Melton Constable, Norfolk (1797-1859): his bookplate inside upper cover.

4. London, Sotheby’s, July 20, 1931, lot 5 to G. Wells.

5. Marcel Jeanson (1885-1942), Paris, France, his bookplate, marked MS. 1, on front endleaf. Successful industrialist and one of the most important bibliophiles of the 20th century, Marcel Jeanson assembled one of the finest collections of books on hunting and ornithology, among many other manuscripts and printed books (sale, Sotheby’s, Monaco, 1987, Part I); another part of the collection was sold by Christie’s in 2000 (Part IV).

Text

ff. 1-152v, Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, Roman de la Rose;

ff. 153-181v, Jean de Meun, Le Testament;

ff. 181v-182, Jean de Meun, Codicil.

The Roman de la Rose was one of the most widely read and debated of medieval works. The fact that more than 300 manuscript or manuscript fragments survive is an eloquent demonstration of its popularity. Of the 328 extant manuscripts, 253 are illustrated, a far greater number than any other literary text apart from Dante. It was the pre-eminent poem of chivalric love, and it had a decisive impact on European literature through its influence on Dante, Petrarch, and Chaucer. For nearly 200 years, the scholarship on the Rose has been prolific and it remains just as lively today. Students of art, literature, linguistics, philosophy, politics, and law have all contributed to the scholarly literature. The poem resonates with concerns about authorship, reception theory, gender, sexuality, and more recently with globalism and postcolonialism, not to mention thorny questions of interpretation. In the last half century, as many as 300 books and articles appear every ten years. As a recent scholar put it: “the Rose’s popularity … has never been greater,” and “shows no sign of losing any of its vibrancy.”

Today, most of the 328 manuscripts are in institutional collections; only a few remain in private hands, while several others are still untraced. The appearance, therefore, of any Rose on the market is of utmost interest. This one, as we shall see, is pivotal not only for its textual distinctiveness and the identification of the illuminator by name but also for its place in the context of the emergence of Flemish realism in an important center, that of Tournai.

The poem was begun around 1230 by Guillaume de Lorris and left incomplete, perhaps on his death; it was taken up some forty years later by Jean de Meun, a scholar and translator resident in Paris. Guillaume de Lorris set his allegory of the Lover’s quest to attain the Rose in the framework of a dream, a dream that he declares he had as a twenty-year-old, some five years earlier. The author enters the Garden of Delight, falls in love with the Rose, and explores the nature of love with those personifications who help or hinder him in his endeavor to reach the Rose. Through the course of the poem, he see-saws between hope and despair. This is the earliest sustained first-person narrative and narrative allegory in French. Jean de Meun's continuation on ff. 28v to 152v, four times the length of Lorris’s original poem, changed the nature of the work and extended the range of the debate. Before the Lover finally achieves the Rose, the reader is taken through the sort of semi-encyclopedic compilation so favored in the Middle Ages. Here, however, the traditional assumptions are apparently parodied or even provocatively revised. The tone is often satirical, and the allegory is more evidently erotic. The mix of old and new, the infinite possibilities of interpretation, the evocative descriptions of the beauties of nature, all gave the poem an immediate and continuing appeal.

Some 95 manuscripts are known from the second half of the fourteenth century, when this copy was made. The poem appealed to a wide range of social classes and levels of education. In 1373 Charles V of France (king from 1364-1380) owned no fewer than four copies, while a contemporary bourgeoisof Douai had a copy to leave in his will. With so many manuscripts in circulation, further copies were easily obtained. A contract with a Dijon scribe in 1399 shows that three months was considered adequate for writing the text (see P.-Y. Badel, Le Roman de la Rose en XIVe siècle, Geneva, 1980). At the end of the century, it was the subject of fierce literary debate as the authoress Christine de Pizan decried Jean de Meun's attack on women and his arguably blasphemous language. It was printed seven times during the incunable period, first in Geneva in 1481, followed by two editions in Lyons in the 1480s and one edition in Paris in the 1490s.

The texts of both Guillaume’s and Jean’s sections in the Jeanson Rose belong to Langlois’s respective groups I. In the case of the Jean de Meun section, this places it among the much less common – and, according to Langlois, “les meilleurs” (or best) – manuscripts. The text has many features in common with that of two closely related manuscripts identified by Langlois as dependent upon a lost Picard exemplar, and there are obvious Picard features to the language (E. Langlois, Les manuscrits du Roman de la Rose: Description et Classement (1910), pp. 246-47 and pp. 405-410).

The Jeanson Rose differs from those, however, in being one of only nineteen copies to contain additions and moralizing revisions made by a third author, Gui de Mori, a Picard cleric. These were originally written between 1290 and 1330. Gui de Mori added, deleted, and rearranged many passages with the general effect of bringing the love story at the heart of the poem more into line with traditional Christian notions of human and divine love. One of Gui’s innovations was the introduction of an additional allegorical vice, Pride, on the wall of the Garden of Delight. This is one of the passages included in the present manuscript where it occurs at the beginning of the descriptions of the vices (f. 2, l.7).

Illustration

In a magisterial monograph, Dominque Vanwijnsberghe has attributed the illumination of the present manuscript to Jean Semont, an artist active in Tournai from c.1385 until his death in 1414 (see D. Vanwijnsberghe, Moult Bons Et Notables: L'Enluminure Tournaisienne a l'Epoque de Robert Campin (1380-1430), 2007, p. 356, ill.). This artist is also responsible for most of the initials with shining golden grounds and sprays of colored and golden ivy-leaves curling into the margins, a feature that makes the Jeanson Rose particularly appealing. A second illuminator collaborated on the decoration of four gatherings and is responsible for the drolleries on the opening leaf.

Relatively few South Netherlandish illuminators of the era are known by name, which makes the discovery by Vanwijnsberghe all the more remarkable. A document in the testament of a local ecclesiastic Jean Olivier (active 1383-1409) describes a Missal for the use of Saint-Amand written by Jean Cuvelier and illuminated by “Jehan Semonth.” This Missal, dated around 1409 has been identified as Valenciennes Bibliothèque municipal, MS 118, and provides us with crucial evidence around which the career of Jean Semont can now be reconstructed. Other documents describe works that have not been identified, a “tavelet” portraying Saint John the Evangelist in 1413 and a manuscript of baptism in the accounts of the Church of Saint-Brice in 1400-1401. Vanwijnsberghe found no other family members with this surname living in or near Tournai, and he assumes that the artist originated in another, possibly Flemish, town.

In the Missal of Jean Olivier, a full-page miniature of the Crucifixion and eight pages with historiated initials thus provide the sole basis for assembling other works around the artist. These works include a wide range of types of texts and images: a Missal of Saint-Pierre (Lille, Bibl. Mun., MS 807); a Book of Hours (Paris, BnF, MS lat. 1364); another Missal dated before 1414 (St. Trond, Monastery of the Vlaamse Minderbroeders, MS A. 49); an extraordinary Psalter in Poughkeepsie (Vassar College Library, MS 4); a Roman de la Rose in New York (Morgan Library and Museum, MS G. 32); another Livre de prières in Paris (BnF, MS n.a.fr. 4412); and a two-volume secular work including Les Voeux de Paon and the Sept Sages de Rome (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 11191 and 11192).

In spite of the wide variety of texts he illuminated, our artist’s International Gothic style remains relatively consistent. He uses a palette made up of predominantly red and blue. The ivy leaf decoration derives ultimately from Parisian sources. His uncomplicated compositions are not unlike those found in a group of pre-Eyckian panels, such as an Altarpiece with Scenes of the Infancy of Christ (Antwerp, Musée Mayer van den Berghe, cat. No. 359). The Trinity in the Jeanson Rose bears close comparison with the same subject in the documented Missal of Jean Olivier (f. 146). Vanwijnsberghe notes that the same exquisite border decoration with its sparkling gold and crisp ivy leaves is found in all the Jean Semont works, and he speculates that the artist himself may have been responsible for it. Exchanges with the Beaufort Master among pre-Eyckian illuminators and the Master of the Rinceaux d’or are signaled by Vanwijnsberghe, who also lays out the subsequent artistic contributions in Tournai, among which are those by the interesting but less accomplished Master of the Règle de l’Hôpital Notre Dame (Tournai, Bibliothèque de la Ville, MS 24).

The subjects of the miniatures in our manuscript are as follows:

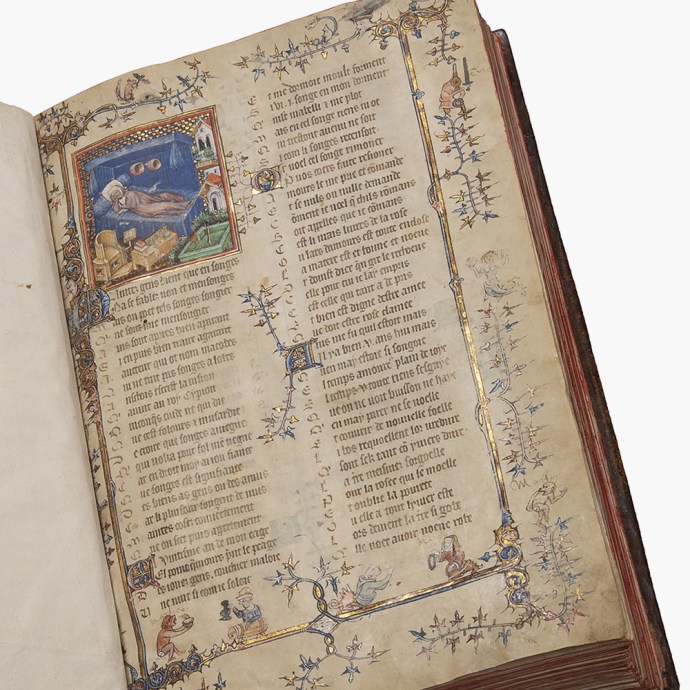

f.1 The Lover resting on his bed, behind him hang two rose chaplets as exchanged by lovers, his sword propped by his pillow, in the foreground a seat, with an attached lectern, and a table with books and the materials and tools, including spectacles, for writing, to the right an enclosed garden around a rosebush, in the background a tall balconied building, the miniature and text within a full-page border illustrated with grotesques as described below.

f.153 Trinity, with God the Father supporting Christ on the Cross, against a checkered ground and within a frame of pink and burnished gold, with a three-sided border with baguettes and ivy-leaf sprays of burnished gold, pink and blue.

f.181v Christ in Majesty, seated on a bench against a checkered ground, one hand raised in blessing the other resting on an orb with a cross, all within a frame of blue and burnished gold.

Illustrations in the 253 illuminated Rose manuscripts vary significantly both in number and subject matter. There are, however, some consistencies: the lover-scribe dreaming that introduces Guillaume de Lorris’s text is commonplace, although as we shall see his treatment differs from one copy to another. Many fourteenth-century copies include a sequence of the Virtues in the garden, such as the other Rose manuscript painted by Jean Semont (NY, Morgan Library and Museum, MS G.32). However, even Rose manuscripts apparently produced in the same workshop may differ in the extent of illustration, the subjects selected and the treatment of individual subjects: see McMunn in Leaves of Gold, Manuscript Illumination from Philadelphia collections, 2001, pp. 210-214. It may be that with a text in the vernacular, and a story that was widely known, illuminators felt confident enough to devise their own interpretations.

The charming, rather literal visualization of the Dreamer-Lover given in the opening miniature of this manuscript seems one such case of a mostly unique interpretation. The Dreamer-Lover (author) lies on his bed, fully clothed, with all that is necessary to write his romance at hand on a chest beside the bed and a chair with an attached arm to hold materials for copying. He is clearly a short-sighted 20-year-old for his reading glasses lie alongside his quills. At the foot of the bed is the enclosed garden where he will be admitted by Fair Welcome and steal a kiss from the Rose on the bush within. The tower in which Jealousy then indignantly imprisons Fair Welcome is shown – in rather everyday terms – in the modest, tall and narrow house in the right background. The rose-bush, secure from love-lorn young men, stands on the balcony. Dr. McMunn has graciously pointed out that several features of this frontispiece are unique: the sword and buckler by the bed of the dreamer occur in no other frontispiece. The Dreamer’s headgear appears on only three figures in Rose frontispieces. The two pink chaplets attached to the bed hangings are also unique. So too are the multi-storied building with rose bushes on the balcony, and the small walled garden surrounded by roses and enclosing a single rose is reminiscent of the one Dangier will later guard from the Lover and Bel-Accueil.

The delightful marginal illustration is also unique. In the center of the bottom margin is a face with big ears, while on the right a monk with a dragon body, legs and a tail gestures in supplication to a nun (named Margo, probably in a fifteenth-century hand). Margo also has a dragon’s body, legs, and a tail, and she holds in her right hand what appears to be a rosary. To their right, the monkey Martin stands on a sprig of trefoil leaves and looks back over his shoulder at the two groups of figures in the bottom margin. On the left of the lower margin the monkey labelled Martico is tossing food from a bowl he holds in his right hand. The brewer in front of him is offering a drink to accompany his food. In the left top margin are a grotesque head and a squirrel holding a branch with a nut and another nut in his mouth. To his right is what appears to be a burrow where, presumably, he intends to store his nuts. Further to the right is a dragon and two grotesque heads. A mermaid, unnamed, in the right center margin holds her traditional attributes of a comb and a mirror. The dark smear around her groin is likely the result of later censorship. Such grotesques are intended to amuse the reader, whether they comment directly or indirectly on the text. Here we might hypothesize that the bodily enjoyment of food and drink on the left is playfully contrasted to spiritual benefits of prayer on the right – a theme that is consistent with most interpretations of the text of the Rose. Similar marginal grotesques exist in other manuscripts by Jean Semont; compare for example a manuscript of Sermons in Tournai (Archives of the Cathedral Chapter, Register 359 B, f. 3) and a Breviary for the use of Tournai (Cambrai, Médiatheque municipal, MS A 104, f. 359), both reproduced in Vanwijnsberghe, figs. 293, 294a, 294b.

Tournai was central to the extraordinary artistic developments evident in the work of Robert Campin (identified with the Master of Flémalle), documented in Tournai from 1406 until his death in 1444, his pupil Rogier van der Weyden, born in Tournai in 1399/1400, and the Van Eycks. The exceptionally thorough iconoclasm in Tournai in the sixteenth century means that little is known of the artistic context of Campin’s mature achievements or Van der Weyden's youth. Vanwijnsberghe’s innovative reconstruction of Tournai manuscript illumination is, therefore, a critical one for the history of art, laying out the artistic context in which these panel painters worked, so crucial for our understanding of the overall practice of painting during the period. Thanks to Vanwijnsberghe, the Jeanson Rose now plays a significant role in this history.

Literature

Published:

Vanwijnsberghe, Dominique. Moult Bons Et Notables: L'Enluminure Tournaisienne a l'Epoque de Robert Campin (1380-1430), Turnhout, 2007.

Langlois, Ernest. Les manuscrits du Roman de la Rose: Description et Classement, Paris, 1910, pp. 246-47 and pp. 405-10.

Further Reading:

Badel, P.-Y. Le Roman de la Rose en XIVe siècle, Geneva, 1980

Arden, Heather M. The ‘Roman de la rose’: An Annotated Bibliography, New York, 1993.

Braet, Herman. “Autour de la Rose, 1990–2005,” in De la ‘Rose’: texte, image, fortune, ed. by Catherine Bel and H. Braet, Louvain, 2006, pp. 459–520;

Braet, Herman. “Annexe bibliographique: autour de la Rose, II,” in Nouvelles de la Rose: actualité et perspectives du ‘Roman de la rose’, ed. by Dulce María González-Doreste and María del Pilar Mendoza-Ramos, La Laguna, 2011, pp. 479–92;

Braet, Herman. “La Tradition critique: un inventaire (bibliographie commentée, 2001–2011),” in Lectures du ‘Roman de la rose’ de Guillaume de Lorris, ed. by Fabienne Pomel, Rennes, 2012, pp. 241-272.

Walters, Lori J., “Illuminating the Rose. Gui de Mori and the illustrations of MS 101 of the Municipal Library, Tournai,” Rethinking the Romance of the Rose: Text, Image, Reception, ed. Kevin Brownlee et Sylvia Huot, Philadelphia, 1992, p. 167-200.

Online Resources

Digital Library of Medieval Manuscripts (The Roman de la Rose Digital Library) https://dlmm.library.jhu.edu/en/romandelarose/extant-manuscripts/

List of Extant Manuscripts of the Rose (DLMM) https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/10CB49KODbQ0Vl_rnJUyLYM0awKu_VXvrJ46QyZsFczk/edit#gid=0

where the Jeanson Rose is listed as “Unknown Location”

The Jeanson Rose is listed in ARLIMA under Gui de Mori as “localisation actuelle inconnue” https://www.arlima.net/eh/gui_de_mori.html