Water Squirt Ring

, West European, 1800-1900

Water Squirt Ring

Description

Fascinating nineteenth century party piece, incorporating an elegant and sparkling ring

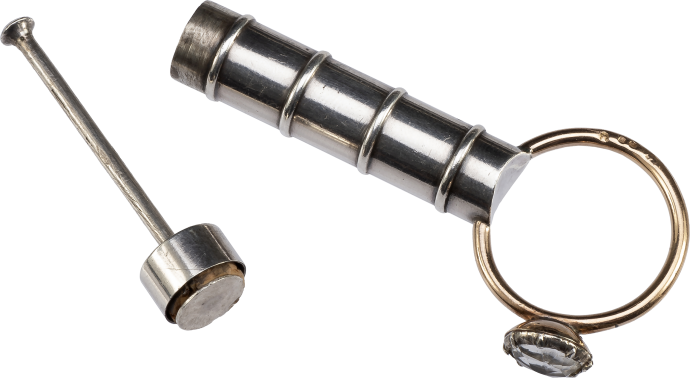

Squirt ring made of a hollow silver cylinder with four ornamental bands and a cap with plunger. This holds the liquid, and when the plunger is pulled out and pushed back in the squirt mechanism is triggered. At the other end is a hollow ring through which the liquid flows and then squirts out of a small hole on the band next to the gemstone. The gold ring, angled to the cylinder, has a tubular hoop and a gold round-shaped cup bezel with a silver-set, facetted rock crystal gemstone. The ring is fully functionable. The cylinder lies concealed in the palm of the hand.

Punched on the cylinder is a swan, the French guarantee mark for the fineness of silver on items of unknown origin (in use from 1893-1970). Along the gold hoop of the ring are four indistinct hallmarks: a helmeted head (?), two rectangular punch marks, one with lower case ‘g’ in the corner, and traces of two illegible punches.

Provenance:

Yves Brasseur (26 February—11 August 2005), Ghent, Belgium, a collector of rings who was a Belgian fencer of Olympic stature, having competed in this sport in the Olympics in the 1960s.

Literature:

The earliest account of a squirt ring dates to about 1770 with the description of a diplomatic incident at the Court of Frederick the Great. The French ambassador M. de Guines belonged to the diplomatic corps in Berlin, the capital of the Prussian Empire. His pompous behavior was widely mocked. Prince Dolgorouki, the Russian ambassador was invited to a gala dinner as a guest of honor with his newly wed bride. She was seated next to the French ambassador whom she squirted with water from a mechanism concealed in the palm of her hand, when he was admiring her jewel. He vowed he would throw a glass of water at her if she continued. The ambassador’s wife ignored his warning, and he in fact put his threat into effect. The guests at the dinner were obliged to keep a discreet silence surrounding this embarrassing occurrence (See: Jones 1898, pp. 493-4; Chadour 1994, vol. II, no. 1648 with further references).

The fashion for such squirt rings appears to have continued into the nineteenth century, although few examples are known. The designs and materials vary: bronze ring with mask of Silenus in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Jones 1898, p. 494; Oman 1930, no. 941). Silenus, the god of wine-making and drunkenness, appears again on a squirt ring in form of a garnet cameo set in an elaborately enameled ring in the Royal Collection (Kirsten Piacenti-Aschengreen and John Boardman, Ancient and Modern Gems and Jewels in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, London 2008, no. 46). An intricately engraved squirt ring in silver-gilt with a sun dial is in the Alice and Louis Koch Collection in the Swiss National Museum, Zurich (Chadour, vol. II, no. 1648). A simpler silver squirt ring in the British Museum has French hallmarks which dates it between 1819-1838 (British Museum OA. 1448). A further nineteenth-century squirt ring with gemstones was sold by Les Enluminures, Chicago (inv. no. 373-3).

By the nineteenth century such rings may have also been used for perfume. Interestingly, the Royal Collection holds two Indian squirt/syringe rings used for rose water which were presented to King Edward VII, when travelling to India in 1875-76 as Prince of Wales (RCIN 11532 and 11395).