Printed Book of Hours (use of Rome)

, France, Paris, Germain Hardouyn, c. 1536

Printed Book of Hours (use of Rome)

Description

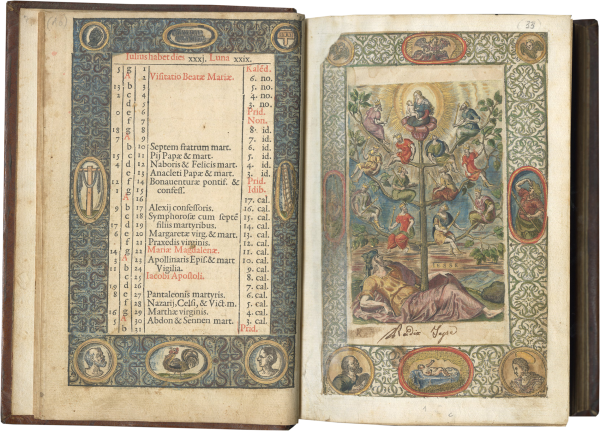

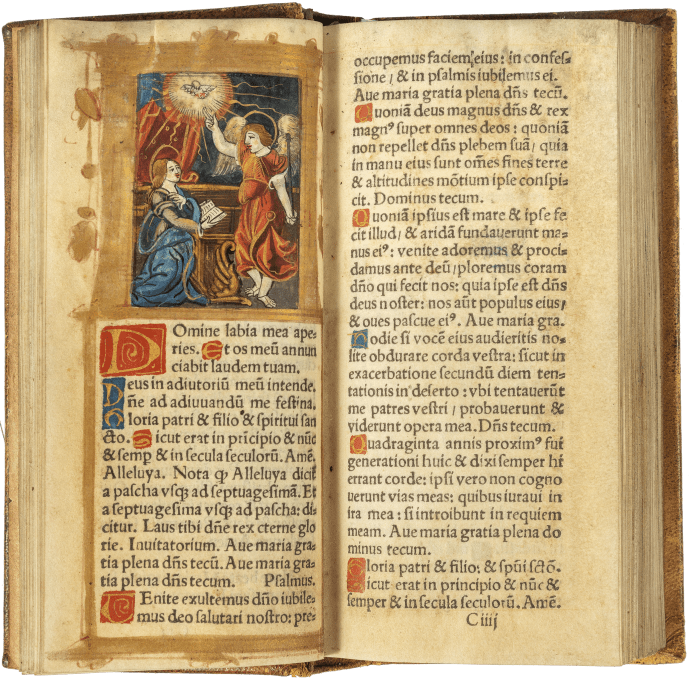

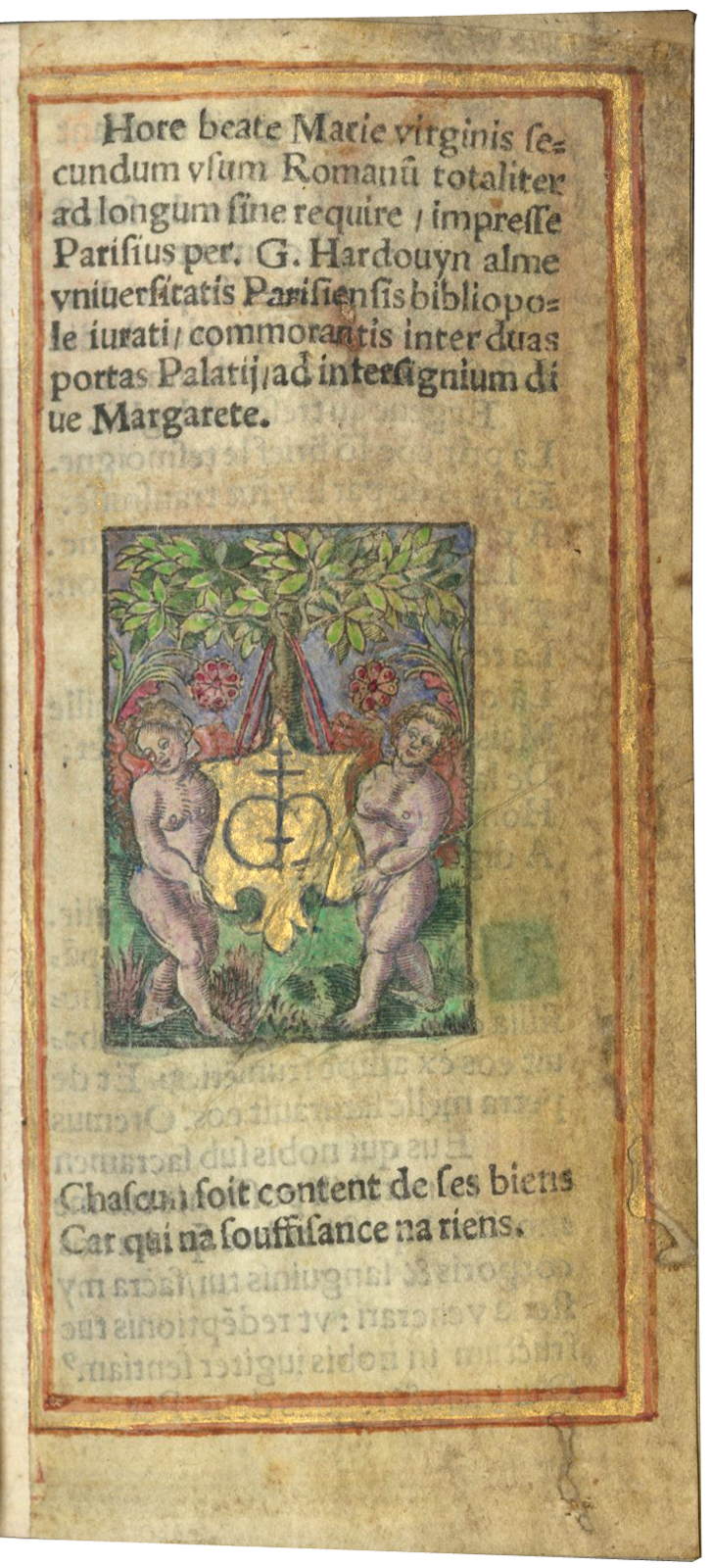

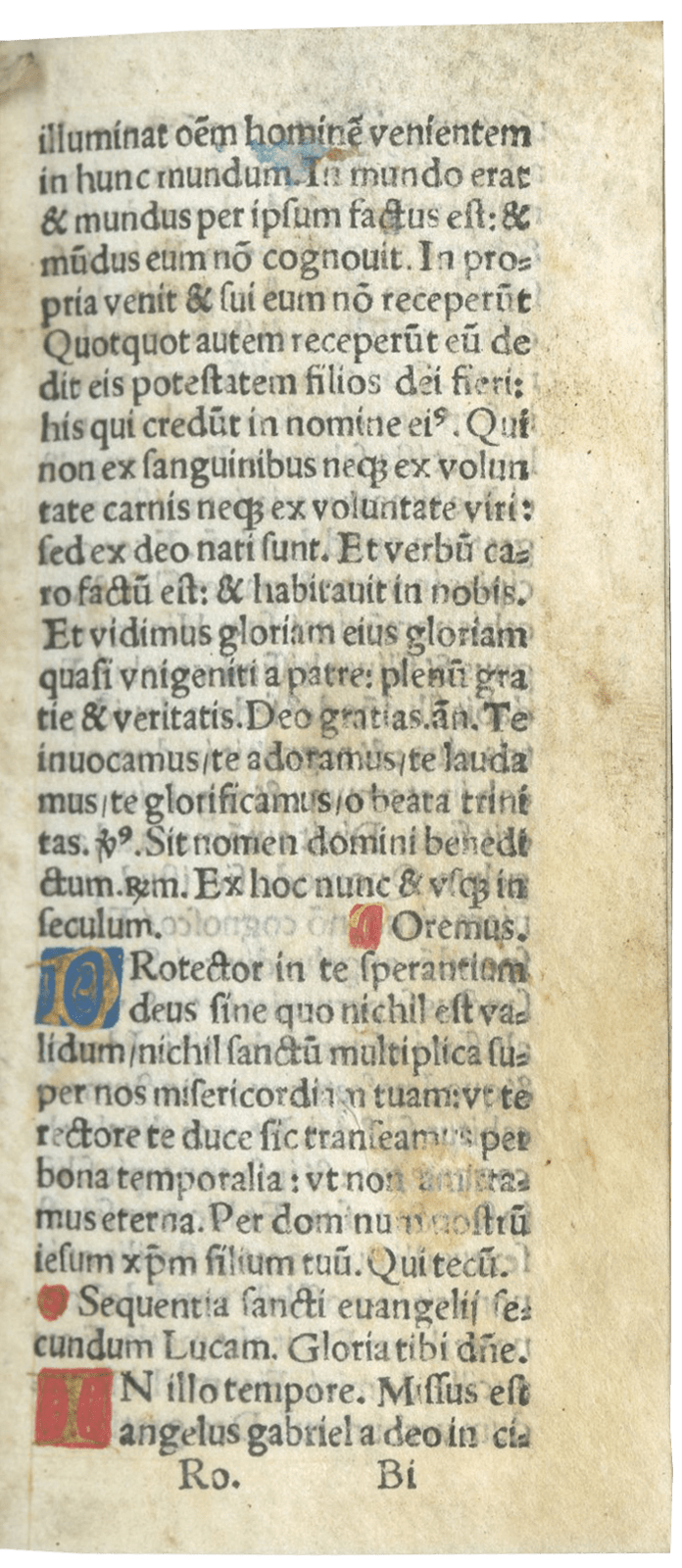

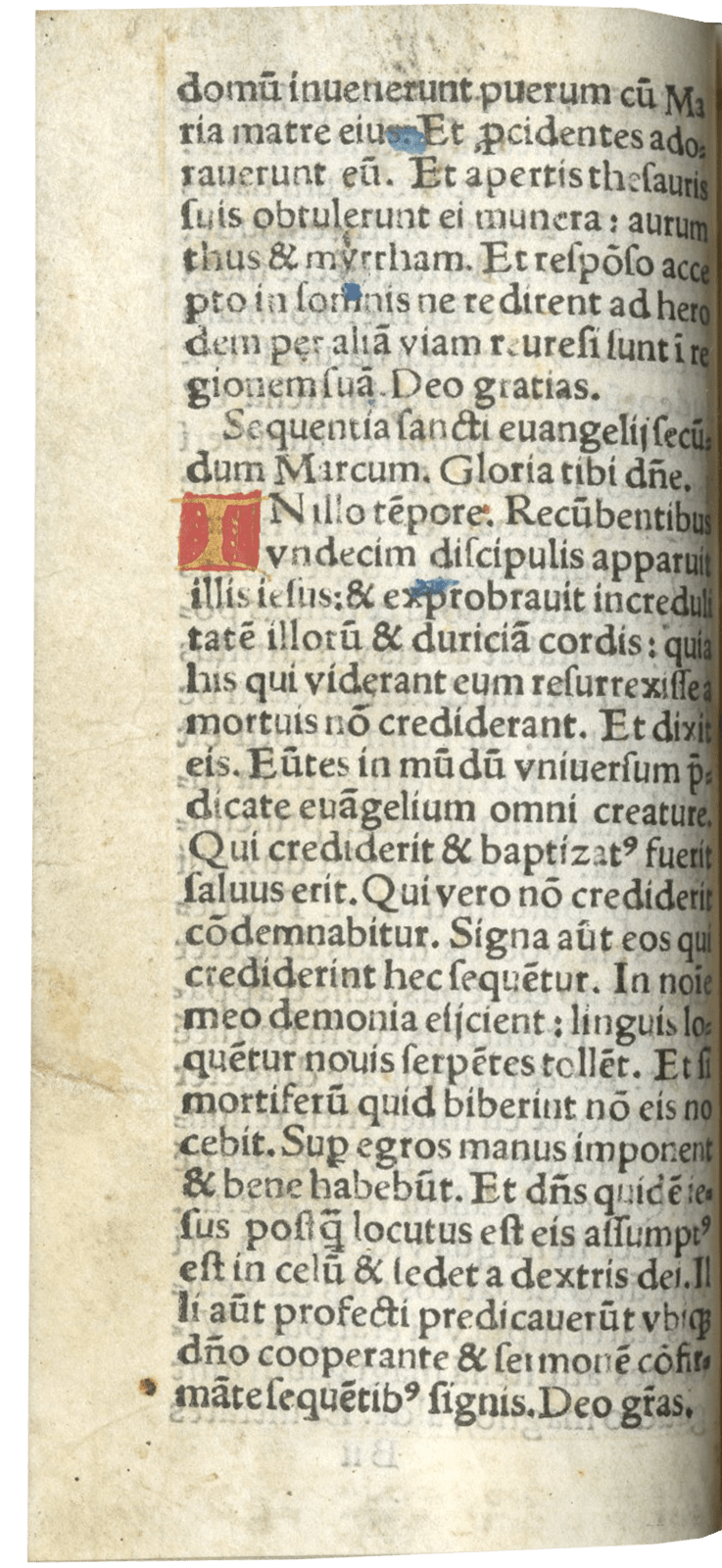

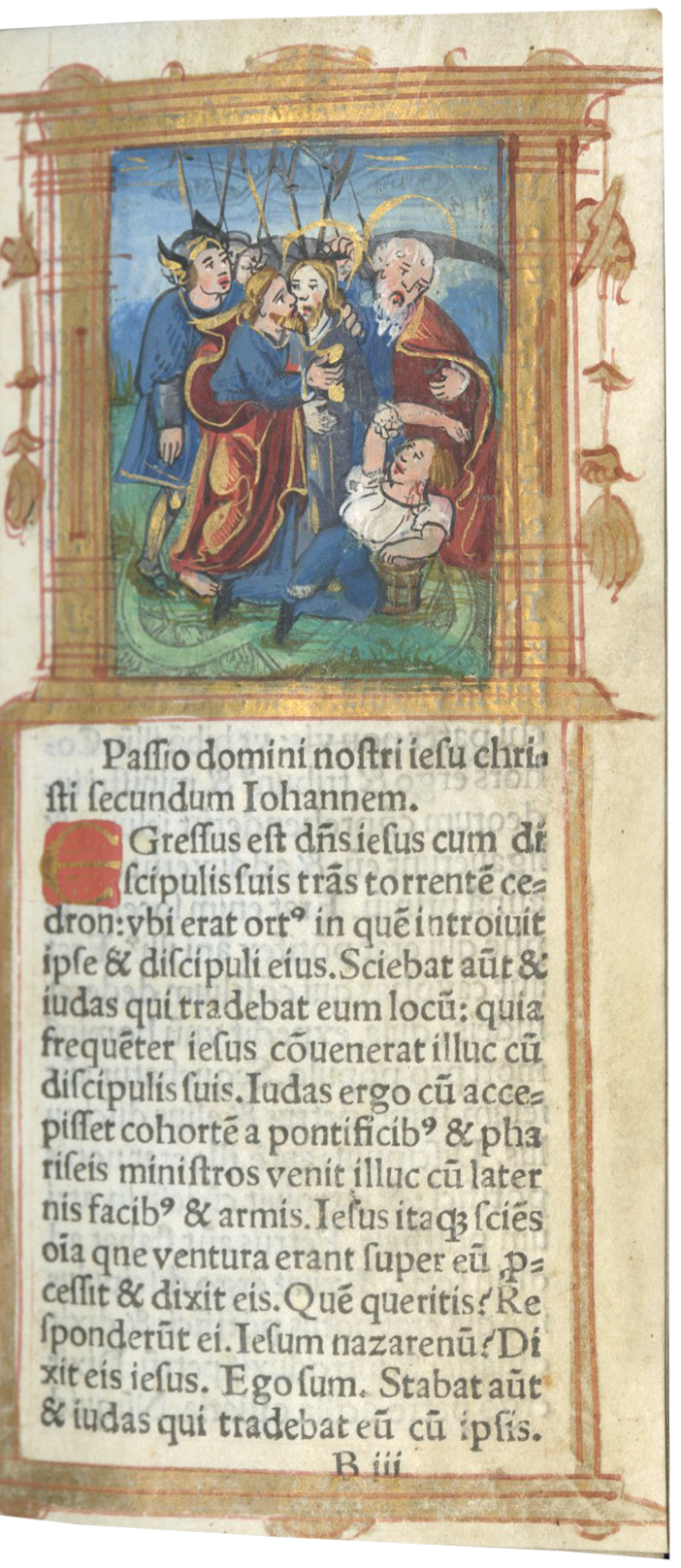

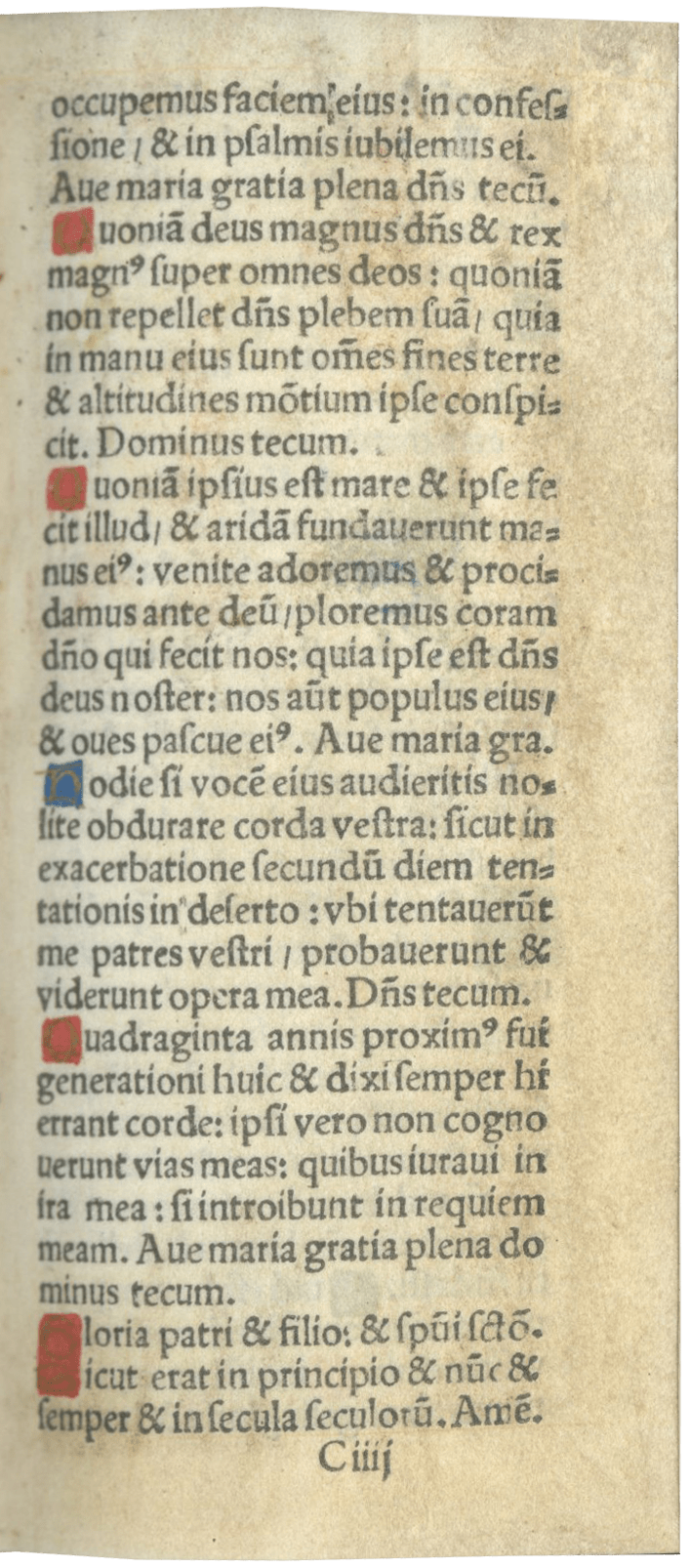

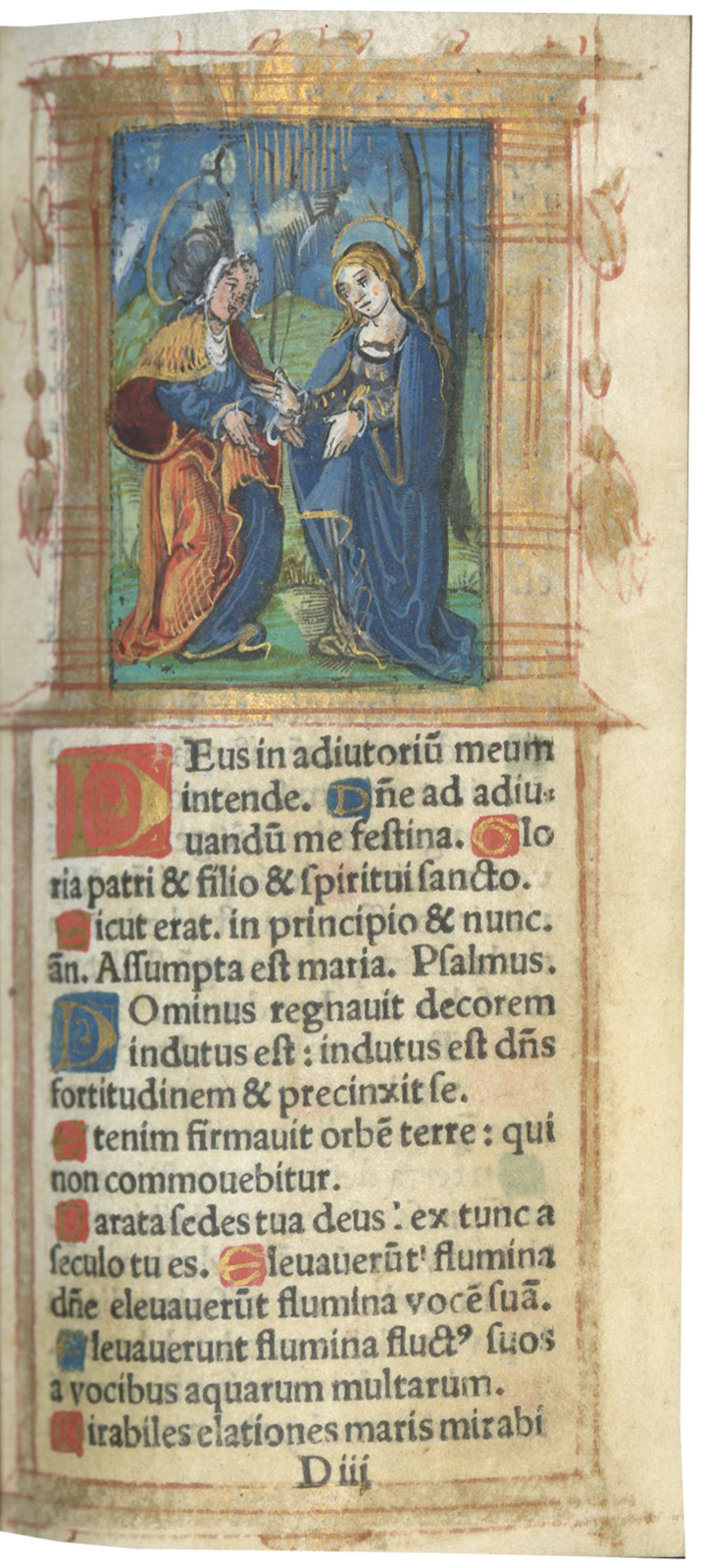

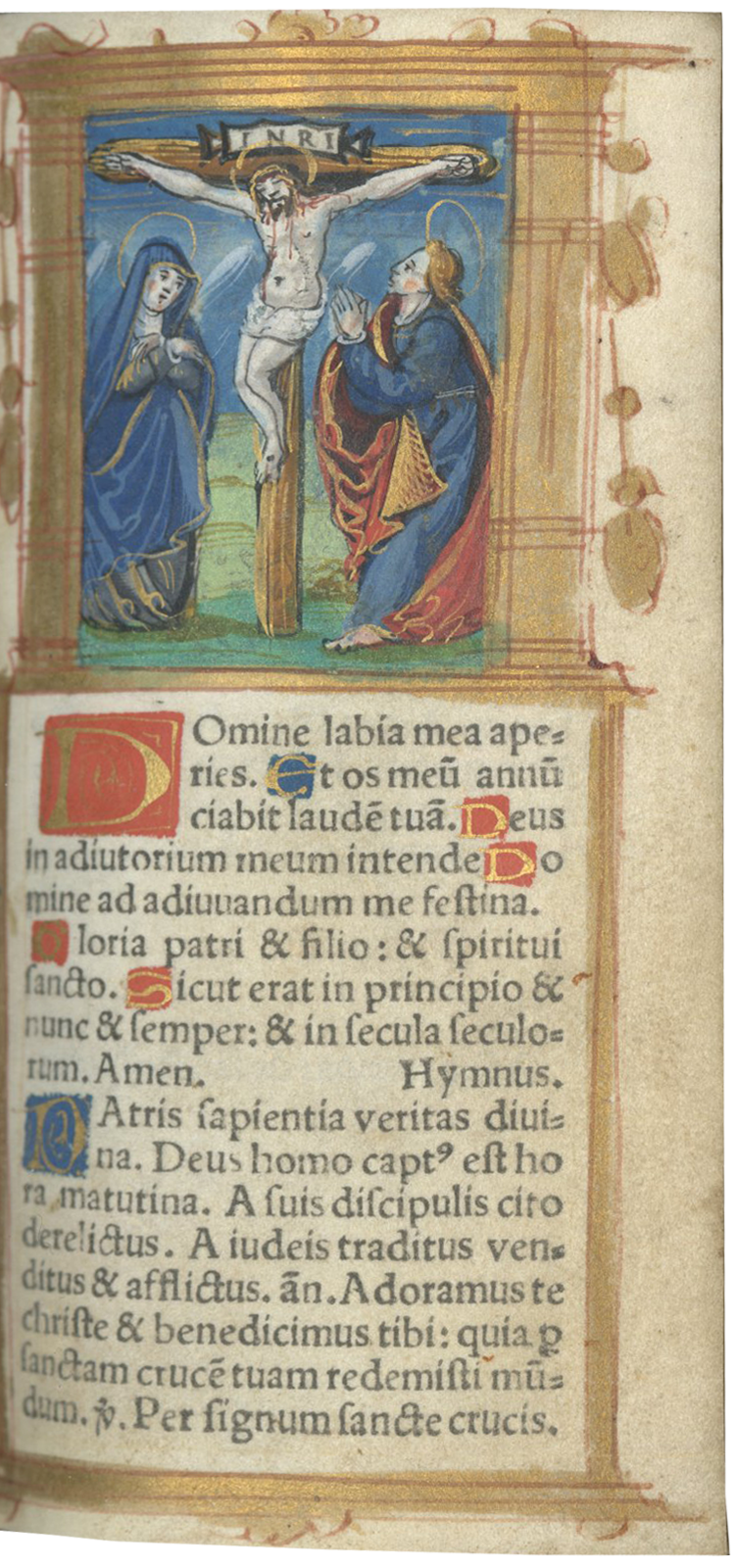

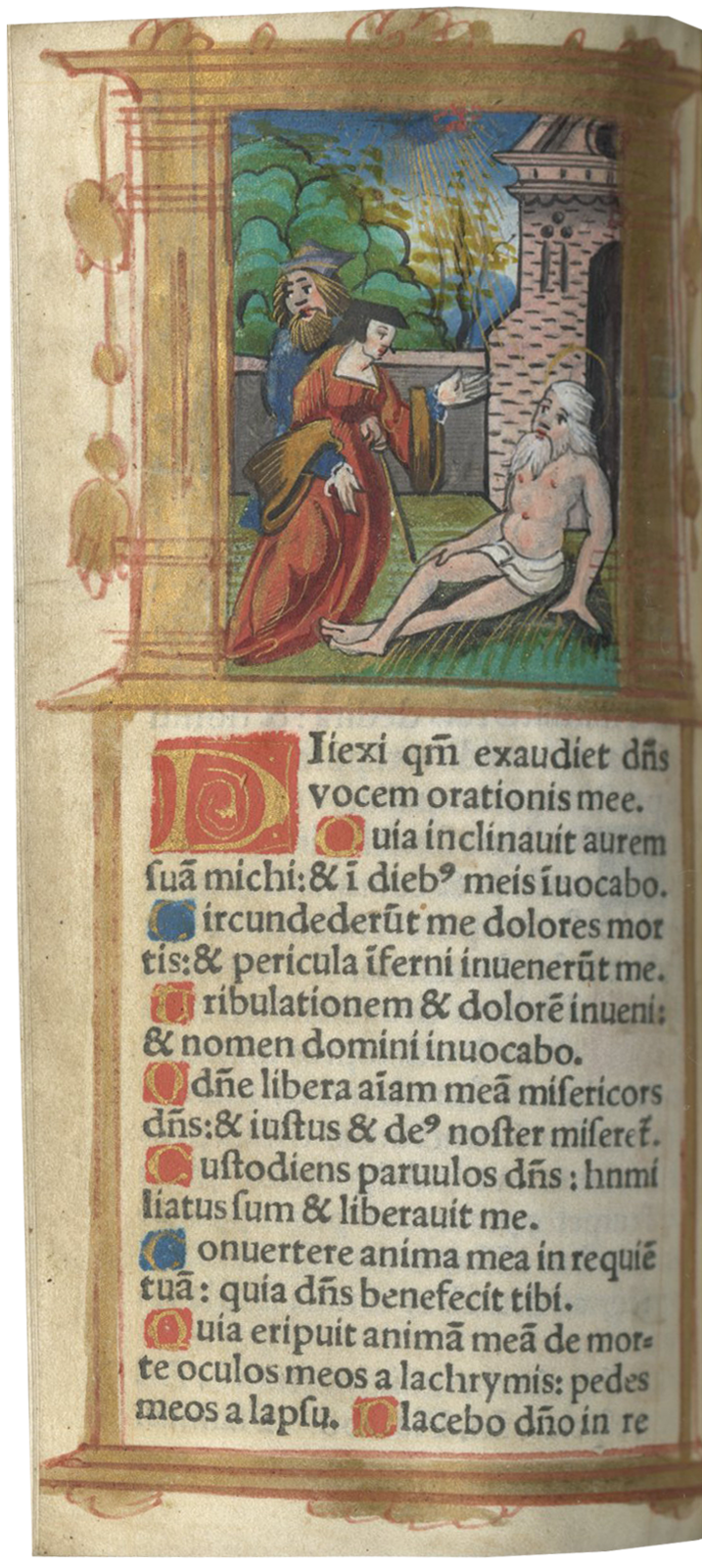

Paris was the epicenter of the production of printed books of Hours from 1485 to nearly 1550. Many of these imprints, like this rare example, consciously imitated illuminated manuscripts. In this particularly appealing volume by the Hardouyn Workshop, fourteen metalcuts are so vibrantly and expertly painted that they are practically indistinguishable from illuminated miniatures. This is a small volume, in a distinctive and unusual format, very narrow and oblong, fitting easily in a pocket to carry about for use in private devotion.

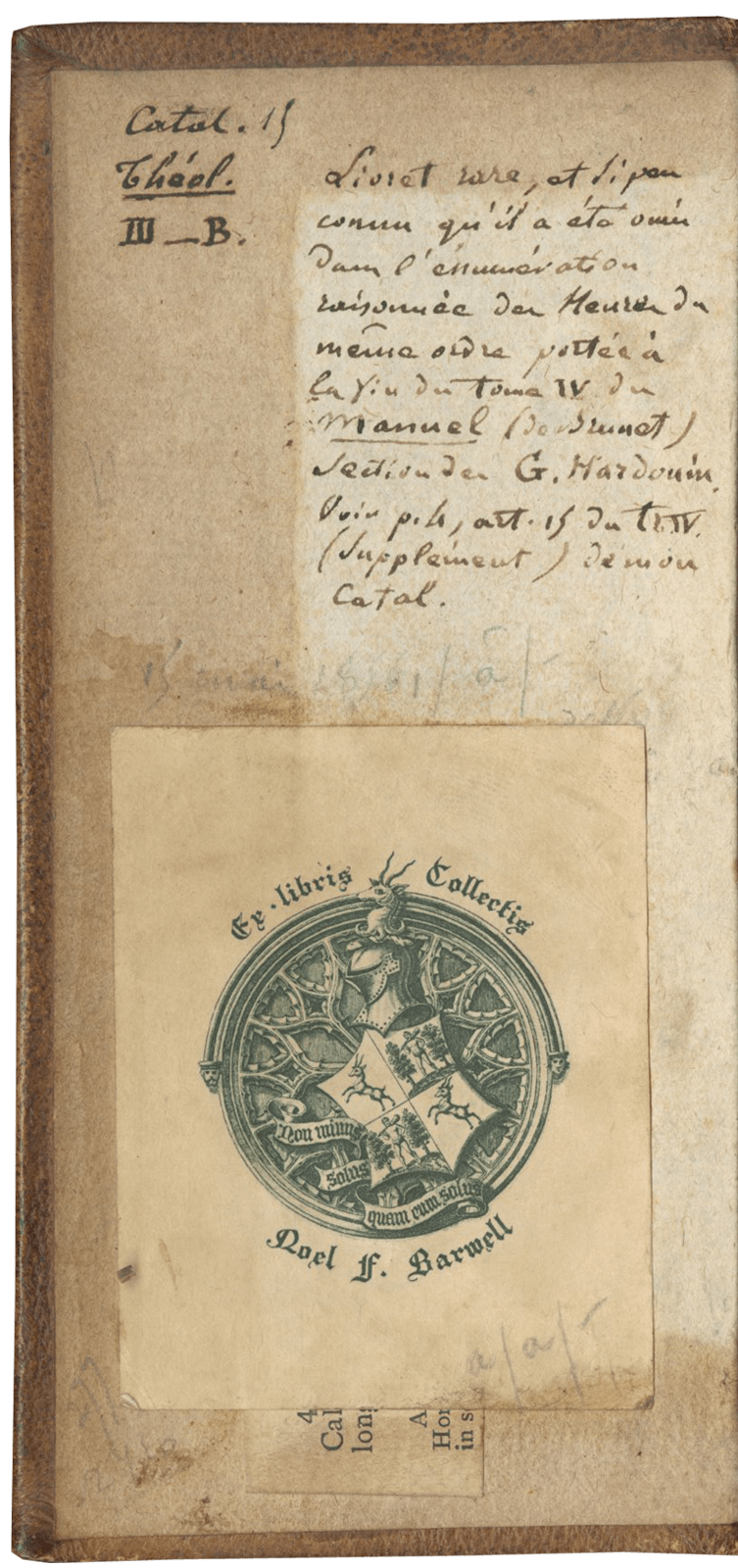

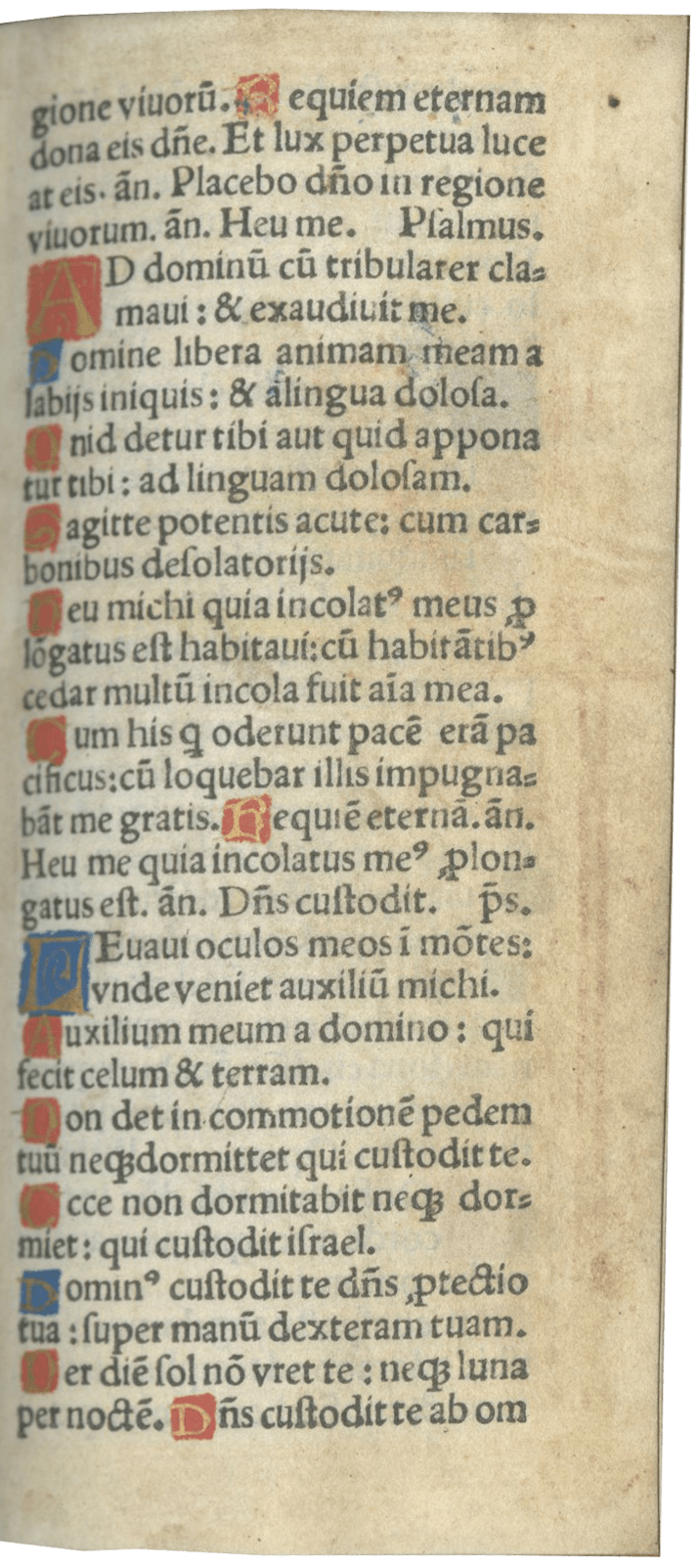

90 ff. (collation: A—K8, L4, M6 [alphanumerical quire signatures on recto of second and third leaves, B–K signatures on recto of first four leaves, L signatures on recto of first three leaves, M signatures on recto of first five leaves]), thirty-two lines printed in Roman font in black ink, (justification 118 x 47 mm), single-, double-, and triple-line initials in gold paint on alternating red and blue grounds, fourteen metal-cut prints, hand-painted with primarily blue, green, and red palette, with gold embellishments, miniatures framed by painted gold doric-style architectural borders that frame text below images, with added gold decoration around borders, some folios with wear, discoloration, and minor damage from handling, f. 42 with loss of paint, faded ink to lower corner; increased wear to last quire, with creasing to parchment from f. 79 onward, f. 90 slightly offset, single unfoliated laid paper flyleaves and pastedowns inside front and back covers, late-nineteenth-century ink notation in French to front pastedown. Nineteenth-century style brown leather covers with gilt-ruled frame, gold tooled spine with seven recessed bands and label: HEURES ANCIENNES, VÉLIN. MINIATURES. Worn with surface losses at joints and edges, small scratches and light abrasions to covers. Dimensions 143 x 76 mm.

PROVENANCE

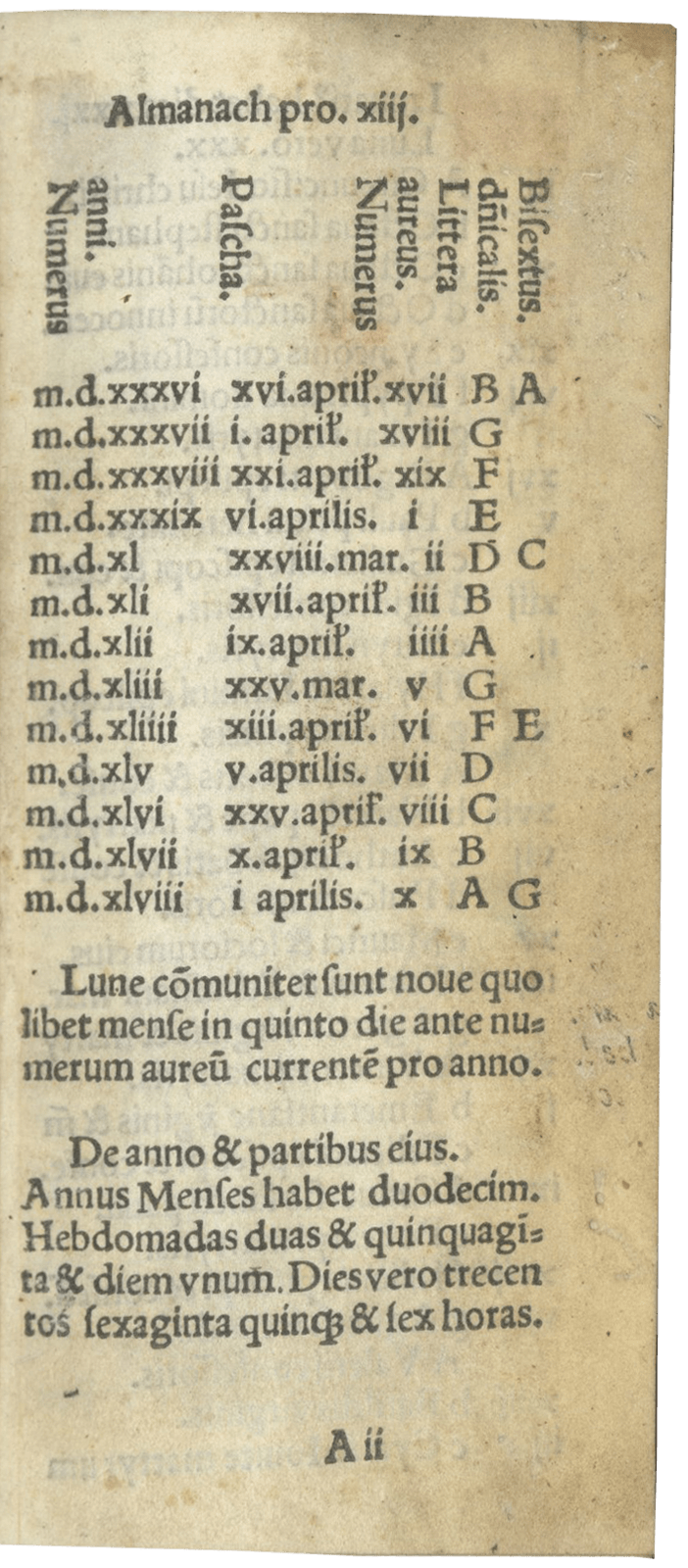

1. Printed in Paris by Germain Hardouyn in the sixteenth century for use of Rome. The almanac for the year 1536–1548 suggests a date of printing c. 1536. Germain Hardouyn (active c.1521–1541), was an illuminator, printer, bookseller, and publisher associated with the University of Paris.

2. Likely sold in Munich by Rosenthal in the 1880s, as listed in the Rosenthal Catalogue XXII, no. 4032. Antiquarian bookseller Ludwig Rosenthal (1840–1928) opened a rare book business in Munich in 1867, which he later partnered with his brothers Nathan and Jacob.

3. Belonged to Noel F. Barwell (1879–[1953]?), his armorial bookplate on the front pastedown. Educated at Cambridge University (Trinity), and listed as member of the Bibliographical Society of Great Britain in 1900 with address in Russell Chambers, Bury Street, W.C.

Text

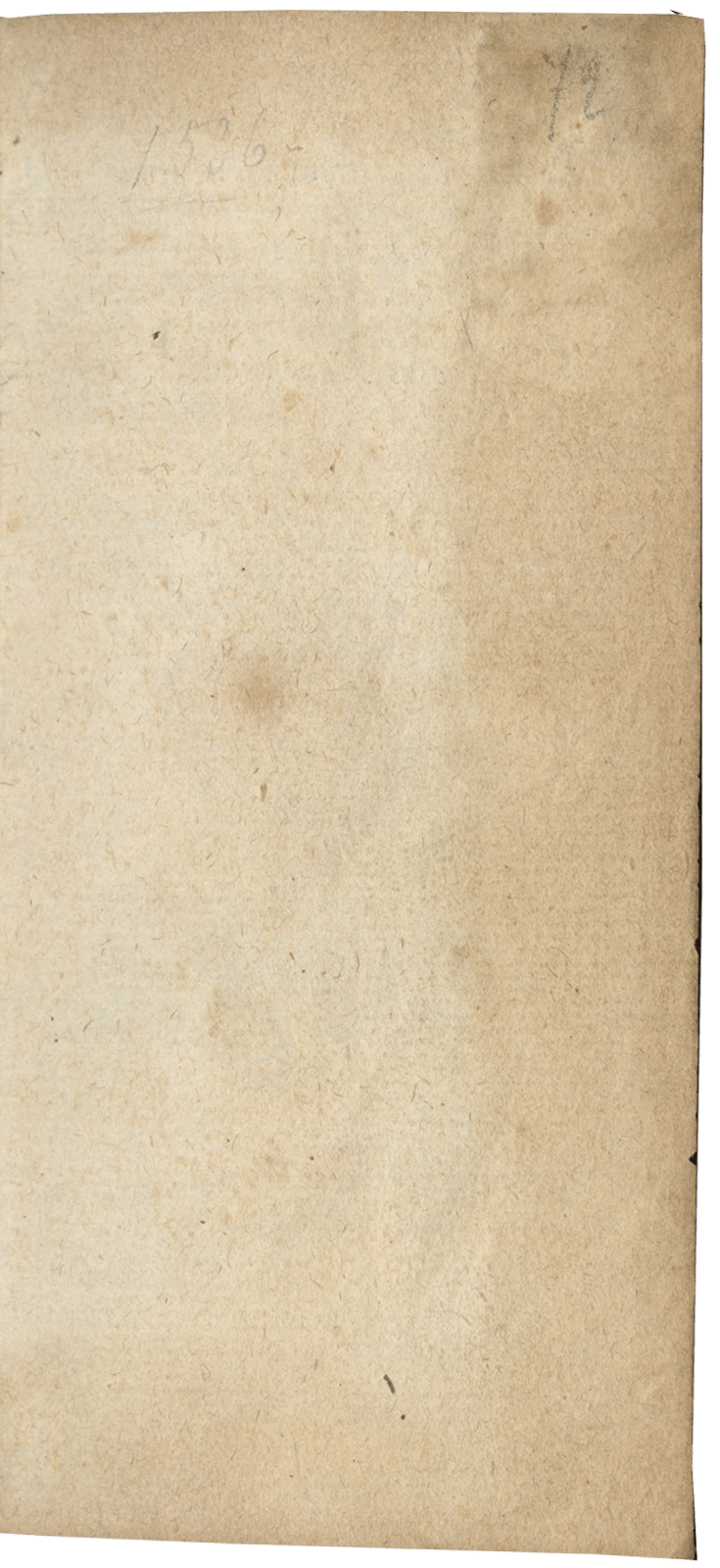

f. 1, Title-page, “Hore beate Marie virginis se//cundum vsum Romanu[m] totaliter// ad longum sine require / impresse// Parisius per. G. Hardouyn alme/ vniuersitatis Parisiensis bibliopo//le iurati / commorantis inter duas // portas Palatii ad intersignium di/ue Margarete.// Chascun foit content de ses biens// Car qui na souffisance na riens./”;

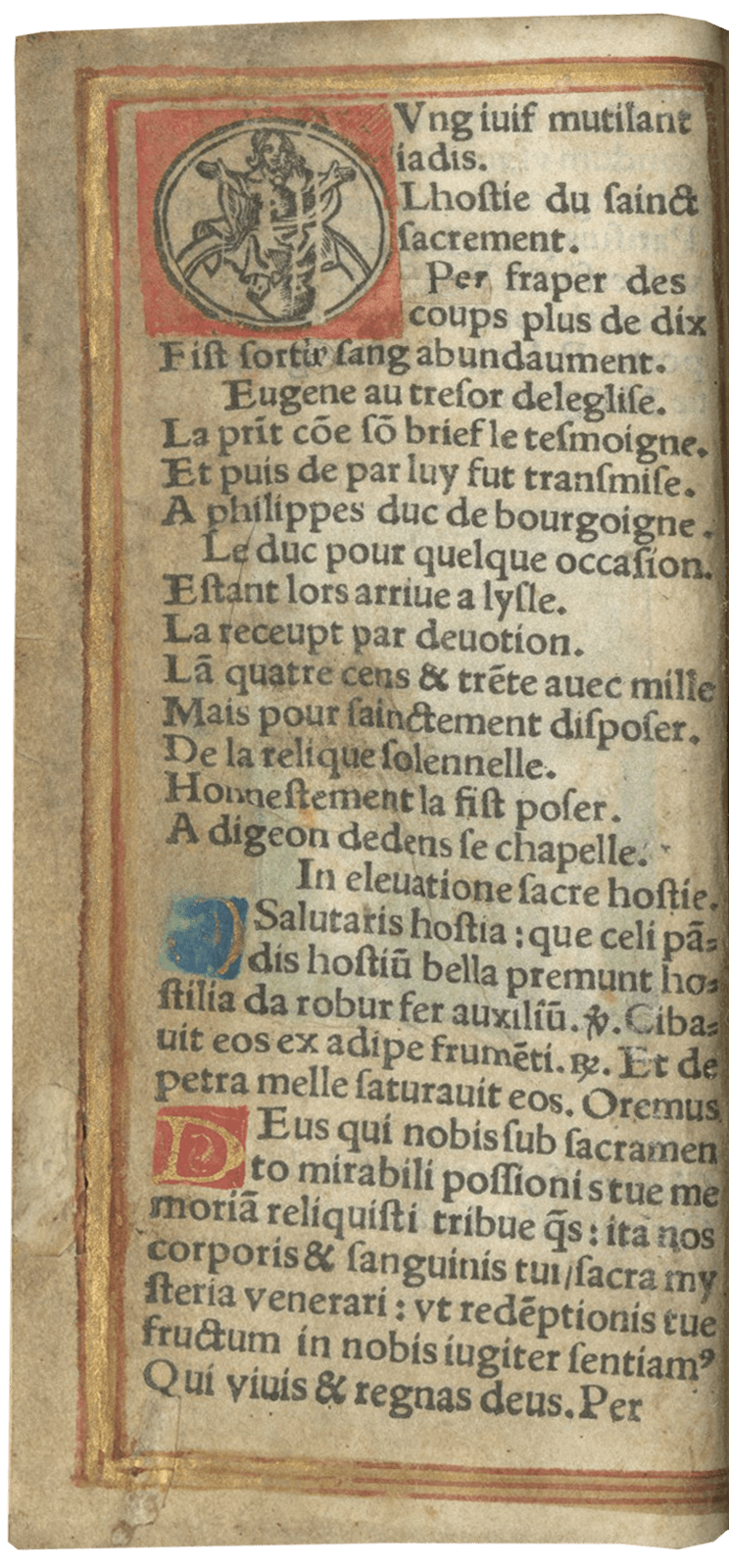

f. 1v, “Vng iuif mutilant iadis. Lhostie du sainct sacrament …; Eugene au tresor de leglise …; In eleuationis sacre hostis …”;

f. 2, Almanac for the years 1536–1548;

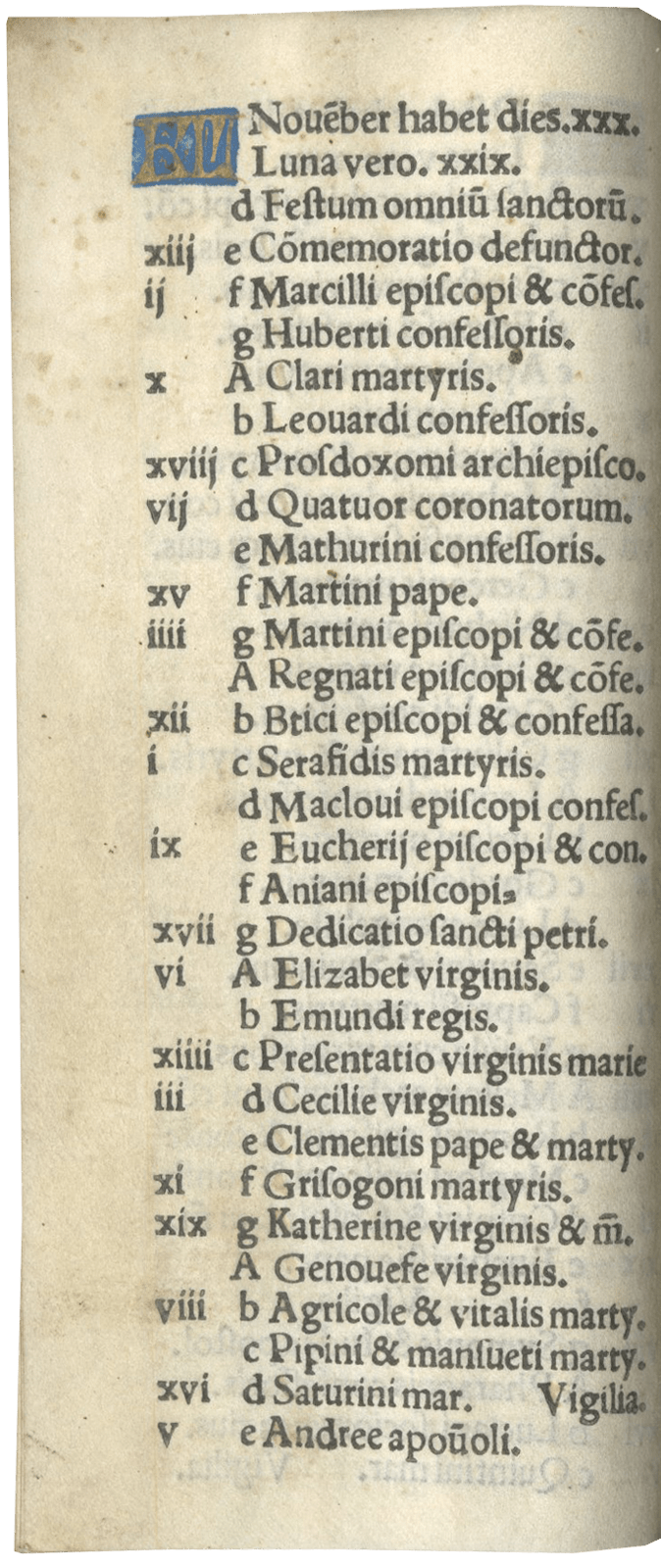

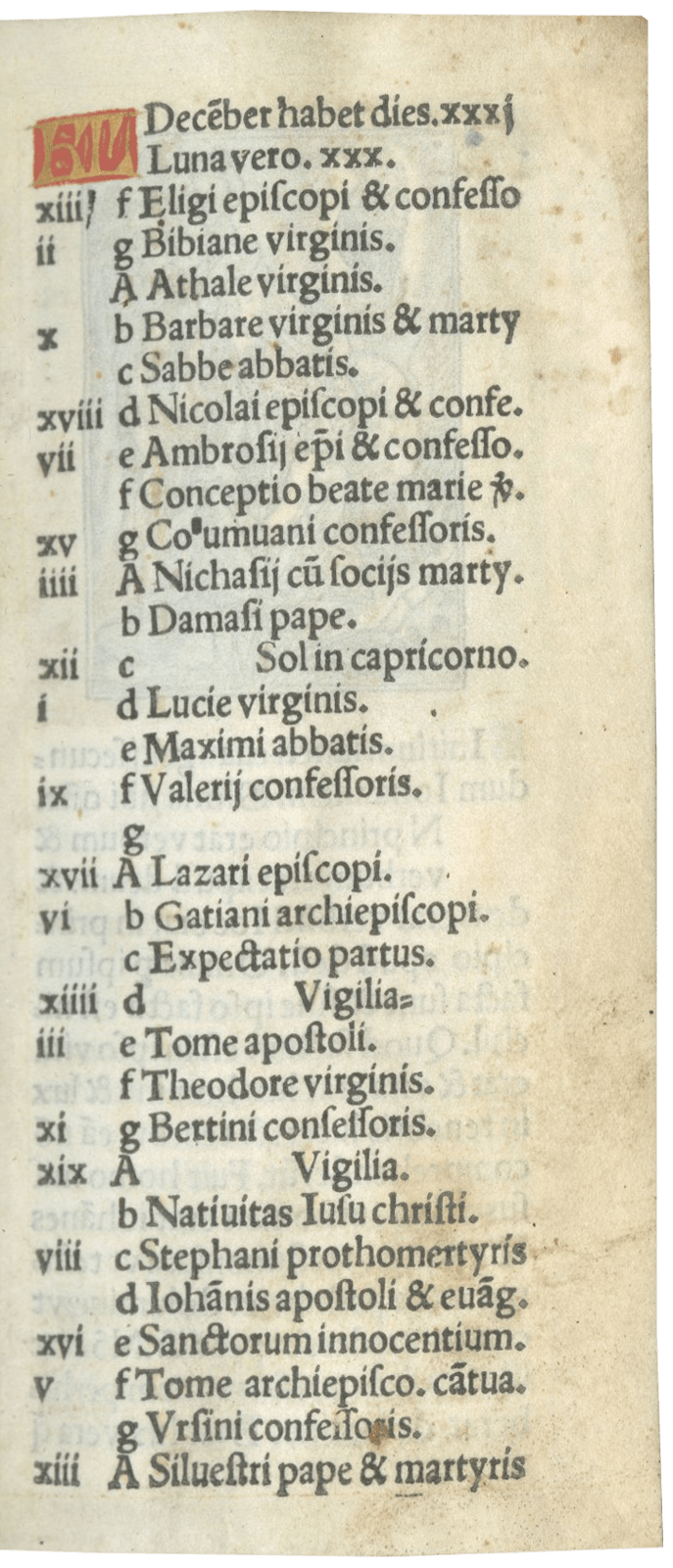

ff. 2v–8, Calendar;

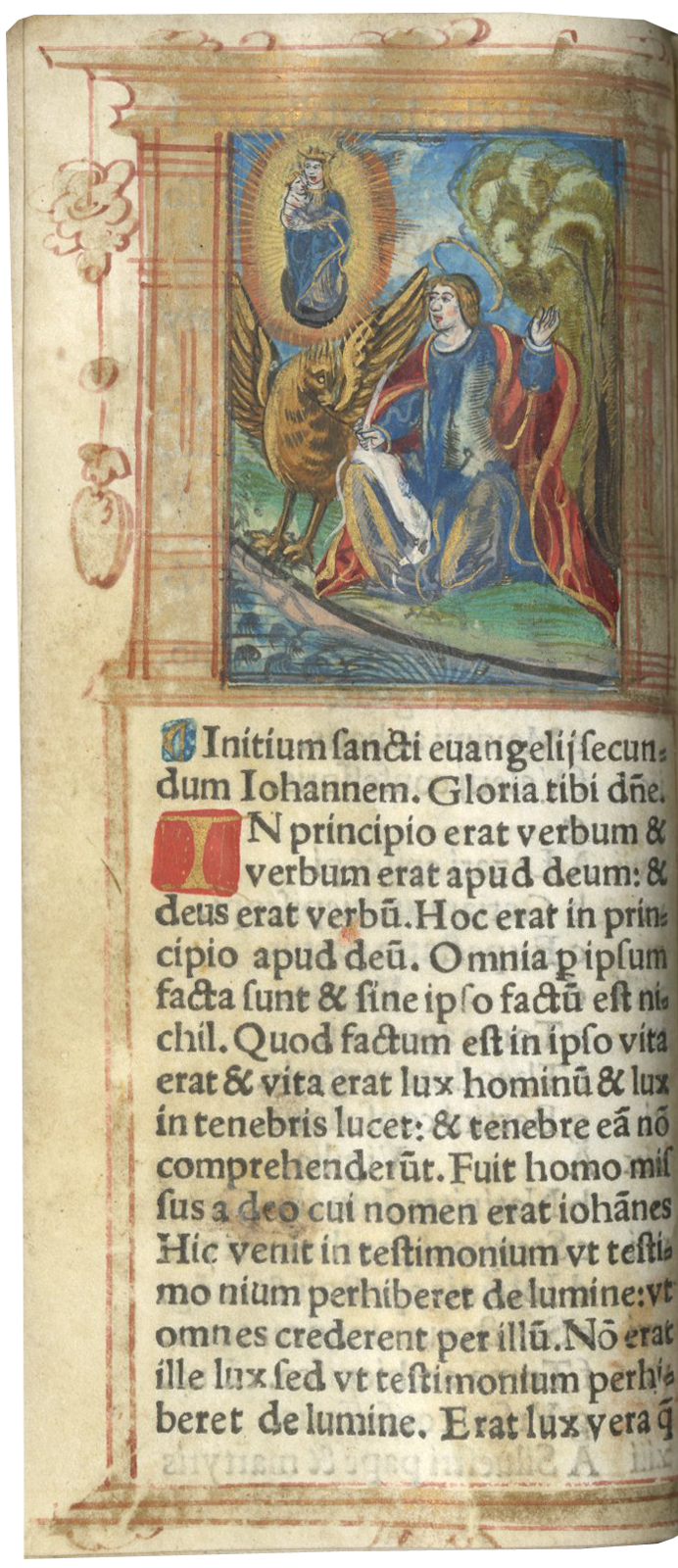

f. 8v, Gospel Lessons, John; f. 9, Luke; f. 10, Matthew; f. 10v, Mark;

f. 11, The Passion from the Gospel of John, followed by prayers;

f. 15v, Obsecro te;

f. 17, O intemerata;

f. 18v, Sequuntur septem gaudia spiritualia …, incipit, “Gaudia flore virginali …”;

f.19v, Hours of the Virgin, use of Rome, with the Hours of the Holy Cross and Holy Spirit worked in: Matins (f. 19v); Lauds (f. 27); Matins Holy Cross (f. 32); Matins Holy Spirit (f. 33); Prime (f. 33v); Prime Holy Cross (f. 35); Prime Holy Spirit (f. 35v); Terce (f. 36); Terce Holy Cross (f. 37v); Terce Holy Spirit (f. 38); Sext (f. 38v); Sext Holy Cross (f. 40); Sext Holy Spirit (f. 40v); None (f. 41); None Holy Spirit (f. 42v); None Holy Cross (f. 43); Vespers (f. 43); Vespers Holy Cross (f. 46); Vespers Holy Spirit (f. 46v); Compline (f. 46v); Compline Holy Cross (f. 48v); Compline Holy Spirit (f. 49);

f. 49v, Salve regina;

f. 50, Antiphona ad beata mariam, incipit, “Alma redemptoris mater”; prayers for each day of the week;

f. 53, Penitential Psalms; followed by Litany and prayers;

f. 61v, Office of the Dead (use of Rome);

f.75, Prayers for the dead, Oratio pro fidelibus defunctis;

f. 75v, Suffrages;

f. 80, Stabat Mater;

f. 81, Seven prayers of Saint Gregory;

f. 81v, incipit “missus est Gabriel angelus…”

f. 84, Hours of the Conception of the Virgin;

f. 88v, Prayer of Saint Augustine, incipit ““Deus propicius esto michi pecatori…”;

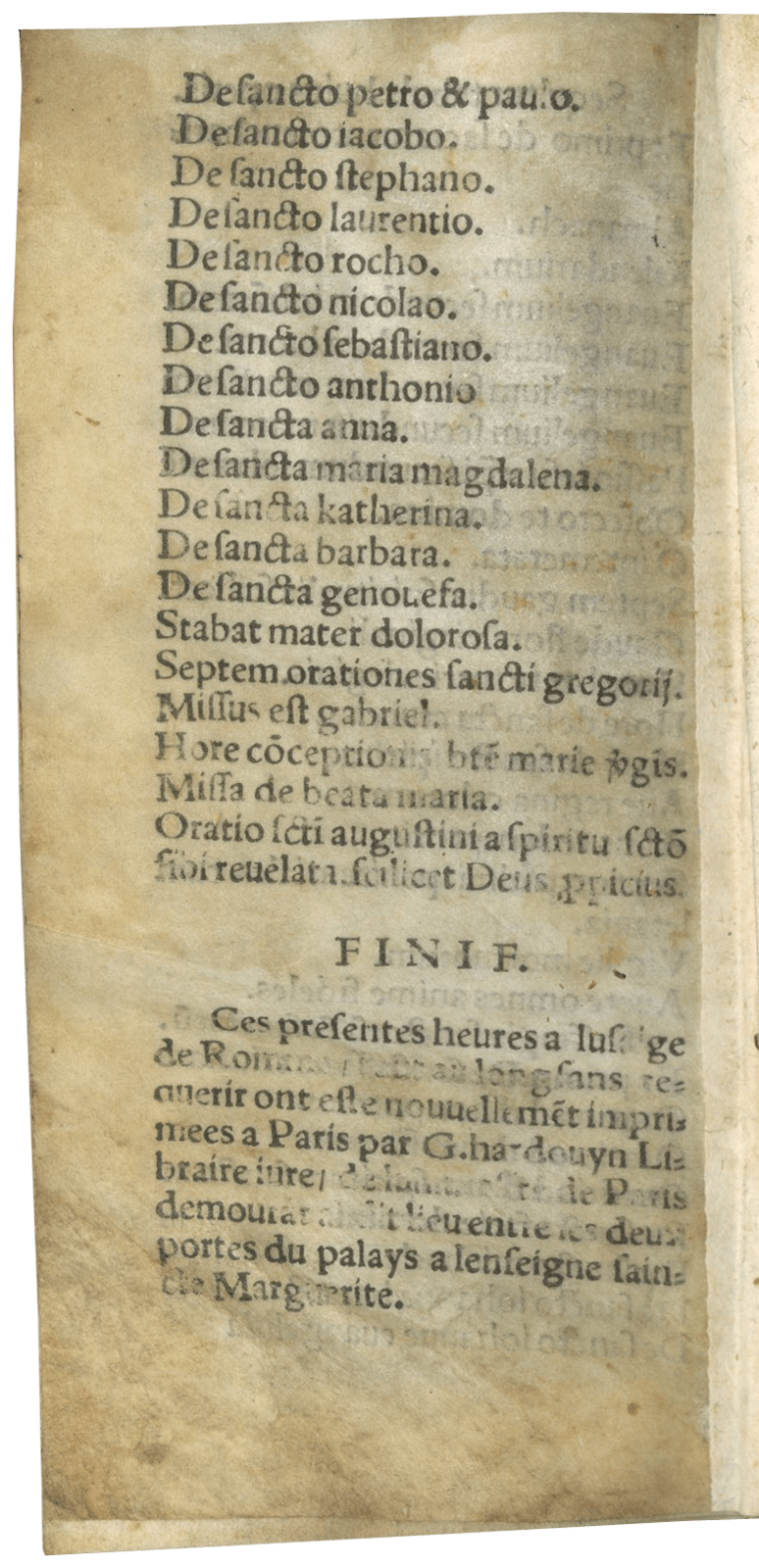

f. 90, Table of contents;

f. 90v, Table of contents concludes “FINIF”; Colophon: “Ces presentes heures a lusaige// de Romme / tout au long sans re-//querir ont este nouvellement impri//mees a Paris par G. hardouyn Li//braire iure de luniuersite de Paris// demourant audit lieu entre les deux// portes du palays a lenseigne sain//cte Marguerite.”

Printed Books of Hours were one of the mainstays of the Parisian publishers and printers; well over 2,000 editions were produced between 1488 and 1568. The new technology of printing, at least in theory, introduced Books of Hours, a prayer book for the laity, to a broader audience. Certainly, the growing urban middle class was one of the chief purchasers of these books. In practice, many printed Books of Hours were finished by hand; in some cases, so luxuriously, that they may have been as expensive as manuscript copies.

Illustration

f. 1, Printer’s device of two winged cherubs holding a shield hung from a tree with flowers in background, red-lined gold frame around text;

f. 1v, Small image (six lines) of miraculous host, not painted except for red frame, red-lined gold frame around text;

f. 8v, John on Patmos with an eagle, and a vision of the Virgin and Child in the sky;

f. 11, The Arrest of Christ;

f. 19v, The Annunciation with the angel Gabriel pointing to the Holy Spirit above the head of the kneeling Virgin Mary;

f. 27, The Visitation of Saint Elizabeth and the Virgin Mary;

f. 32, The Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and Saint John;

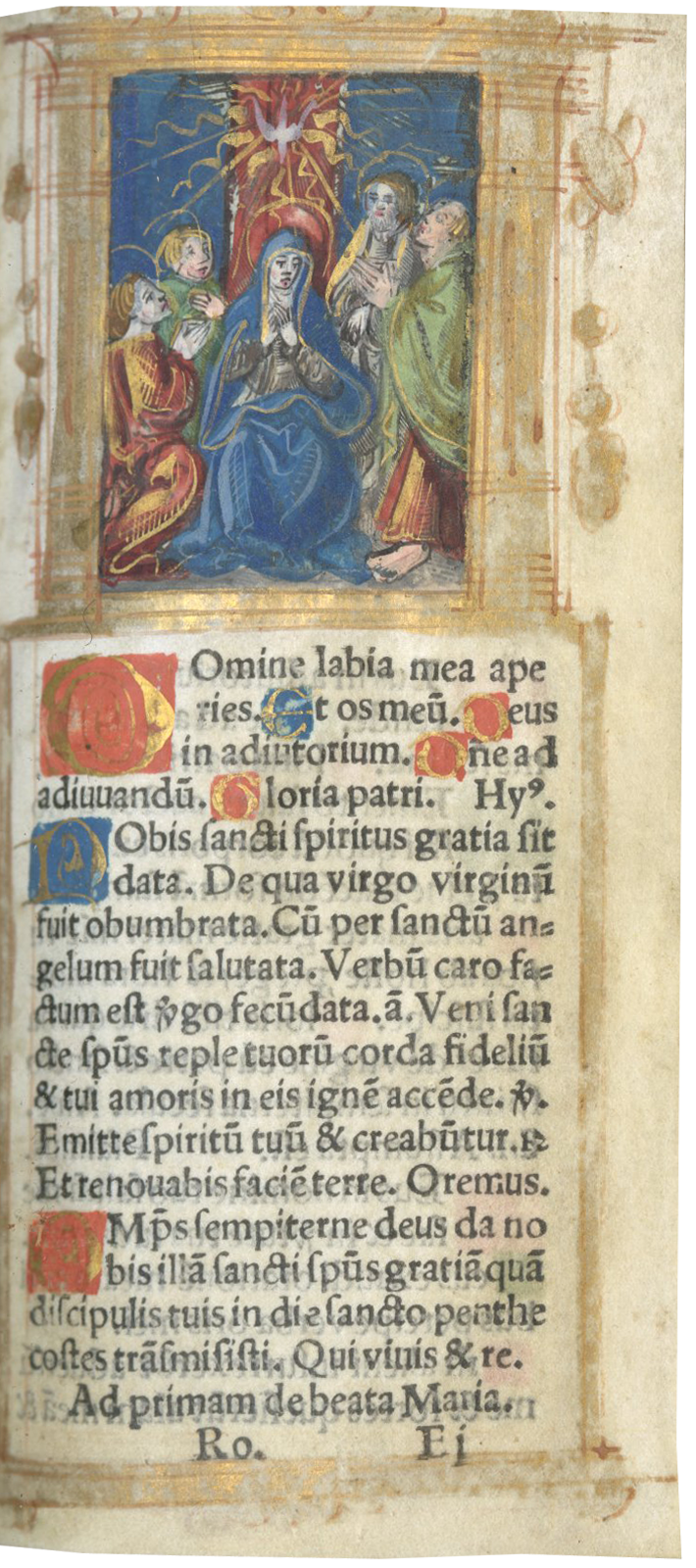

f. 33, Pentecost with the Holy Spirit above the heads of the Virgin Mary and four apostles;

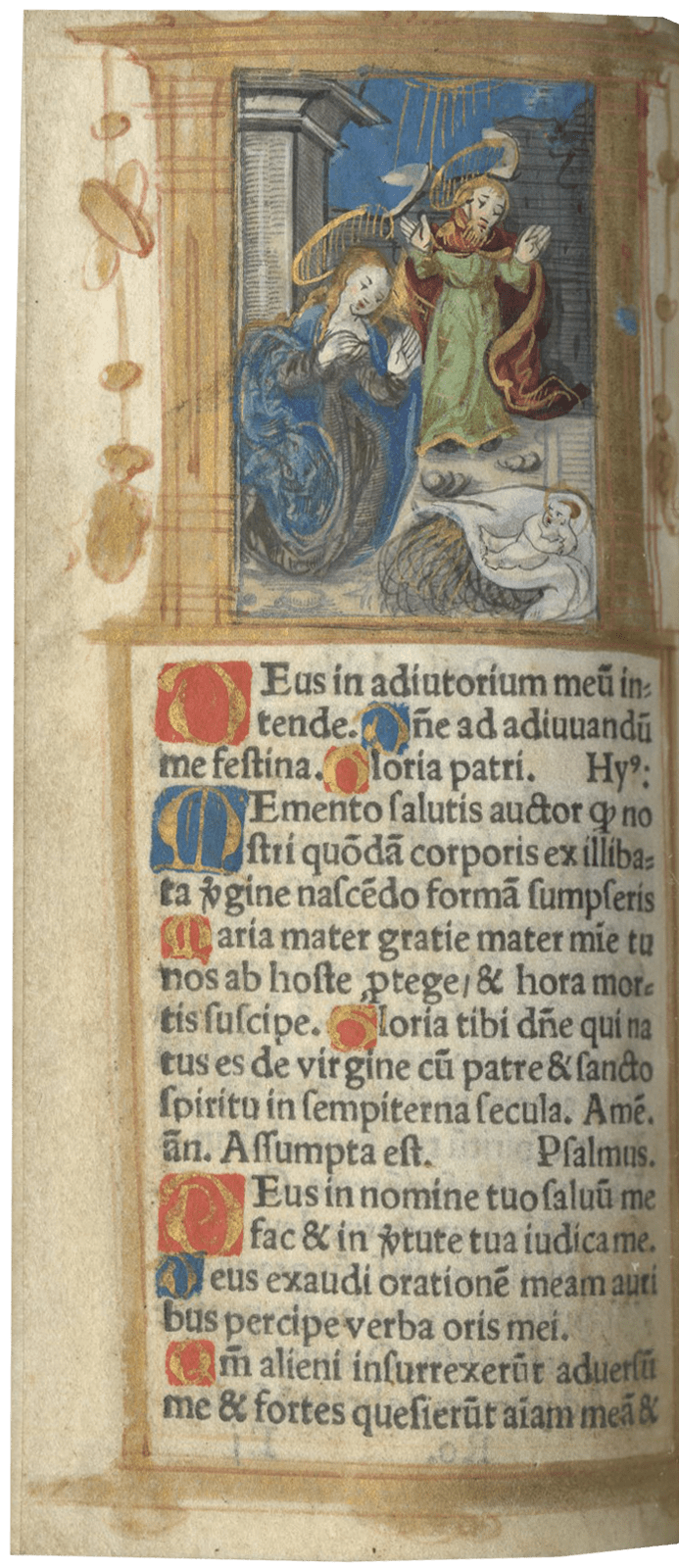

f. 33v, The Nativity with the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph adoring the Infant Christ;

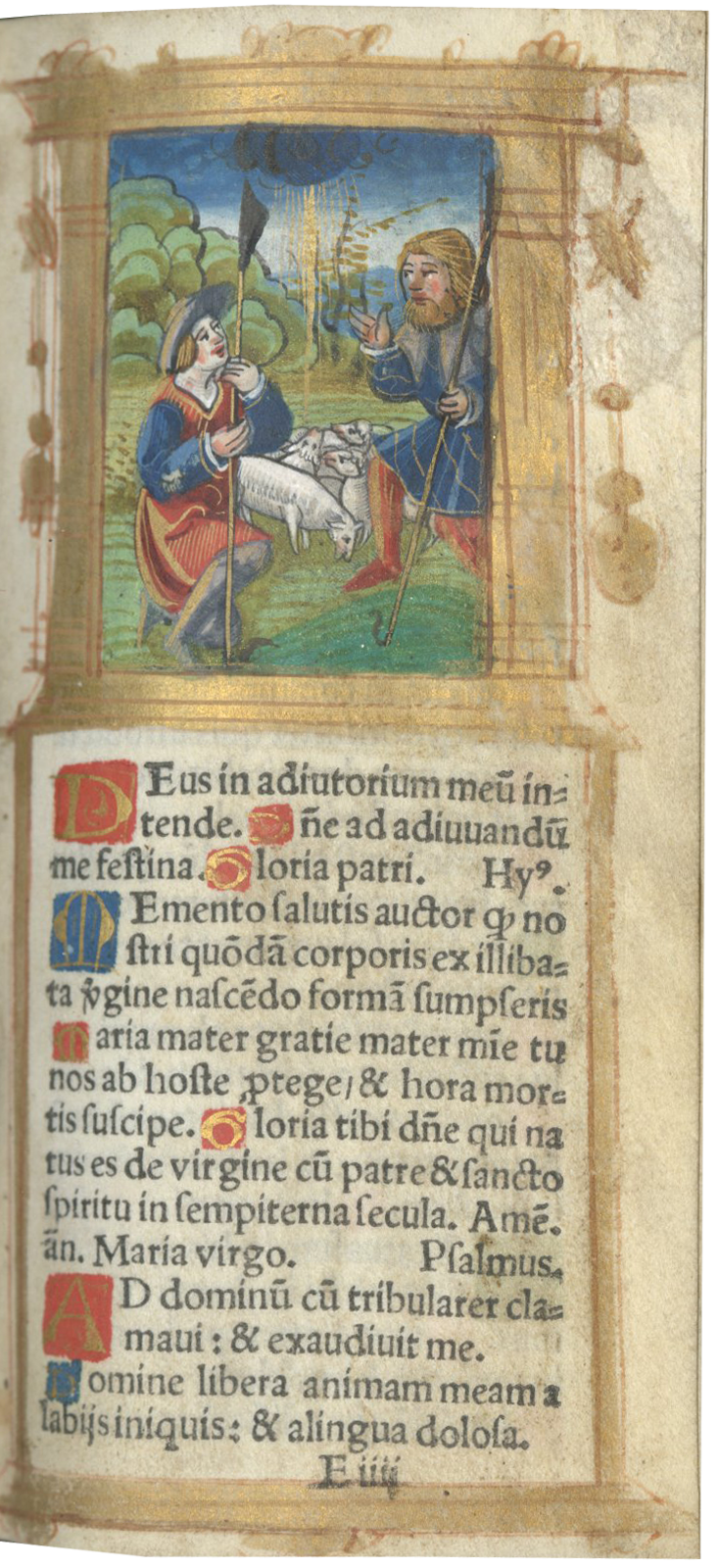

f. 36, The Annunciation to two shepherds tending a flock;

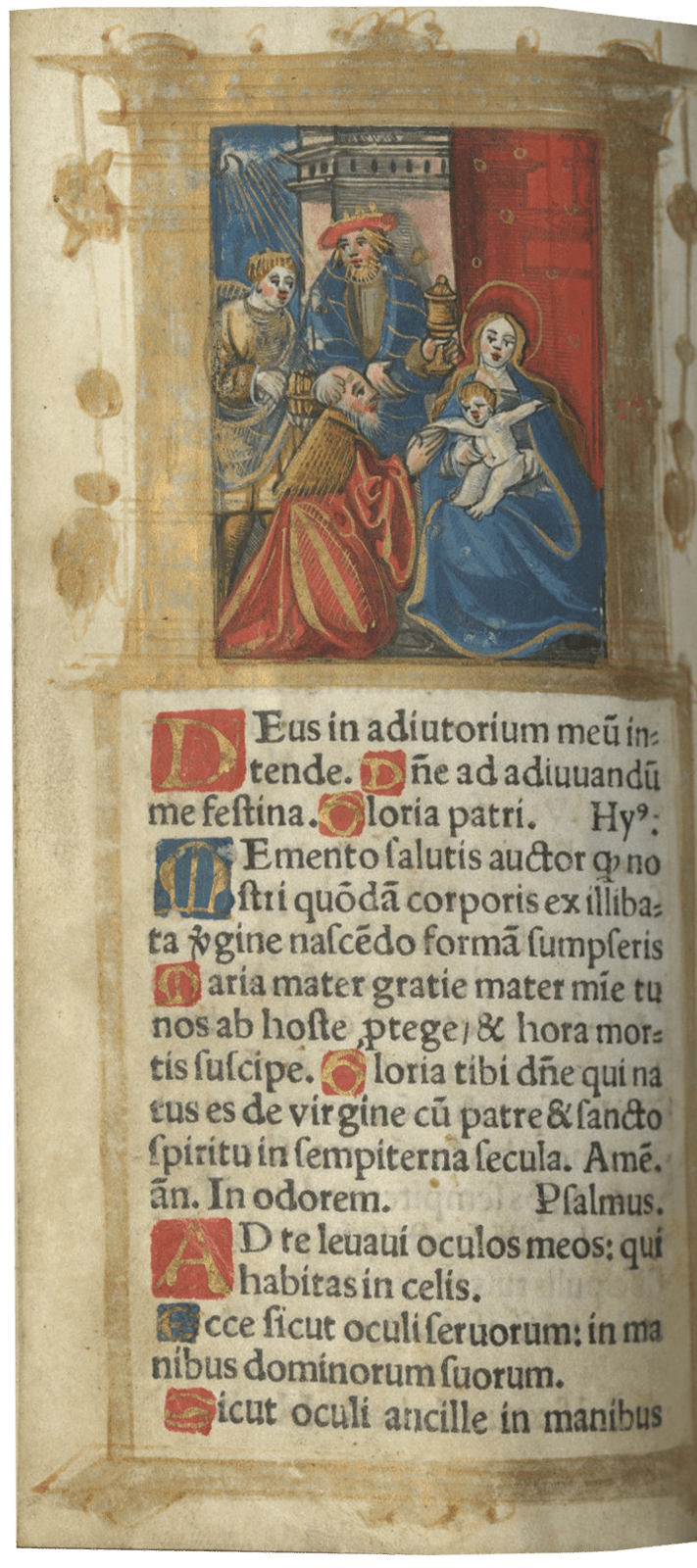

f. 38v, The Adoration of the Magi;

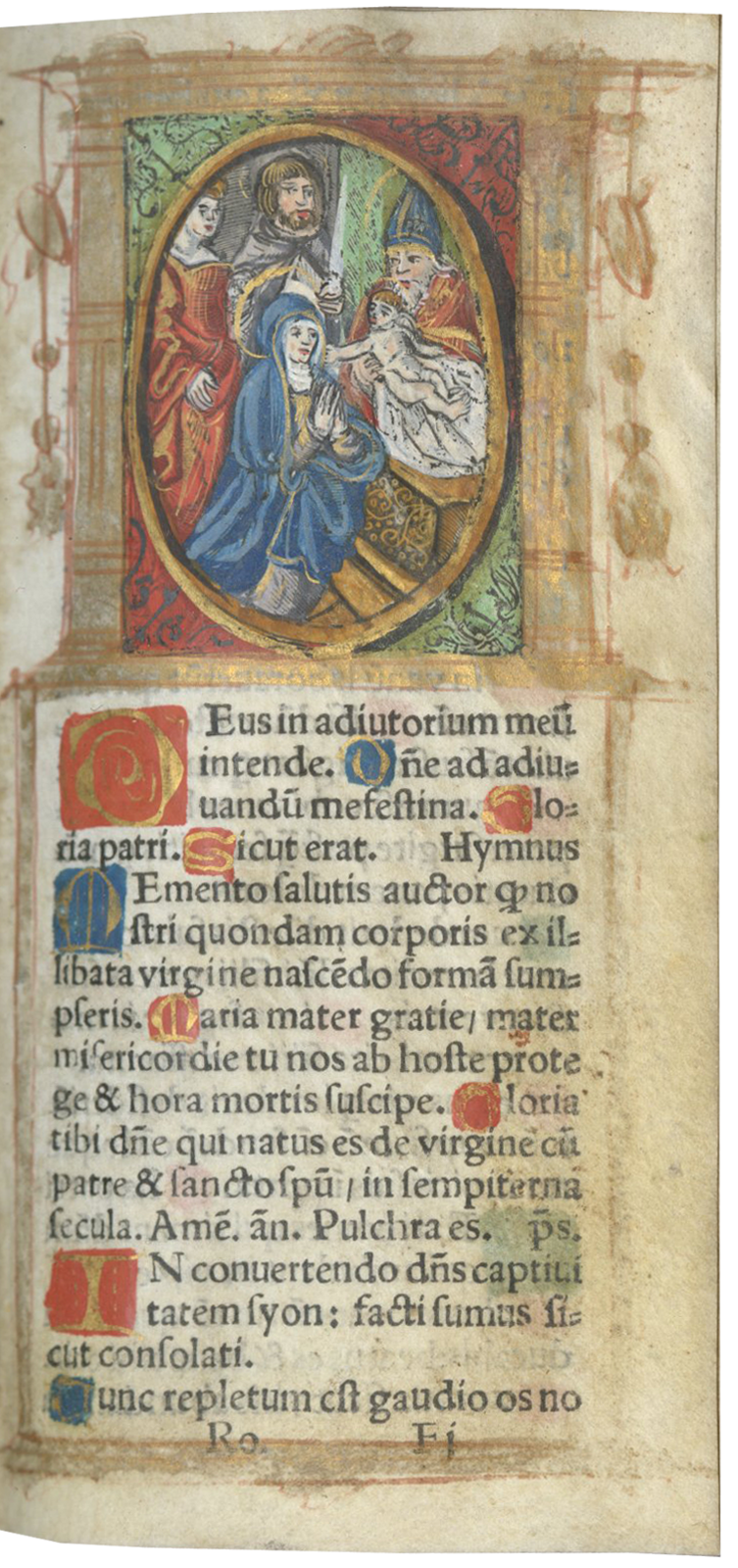

f. 41, Presentation in the Temple, set in a round frame;

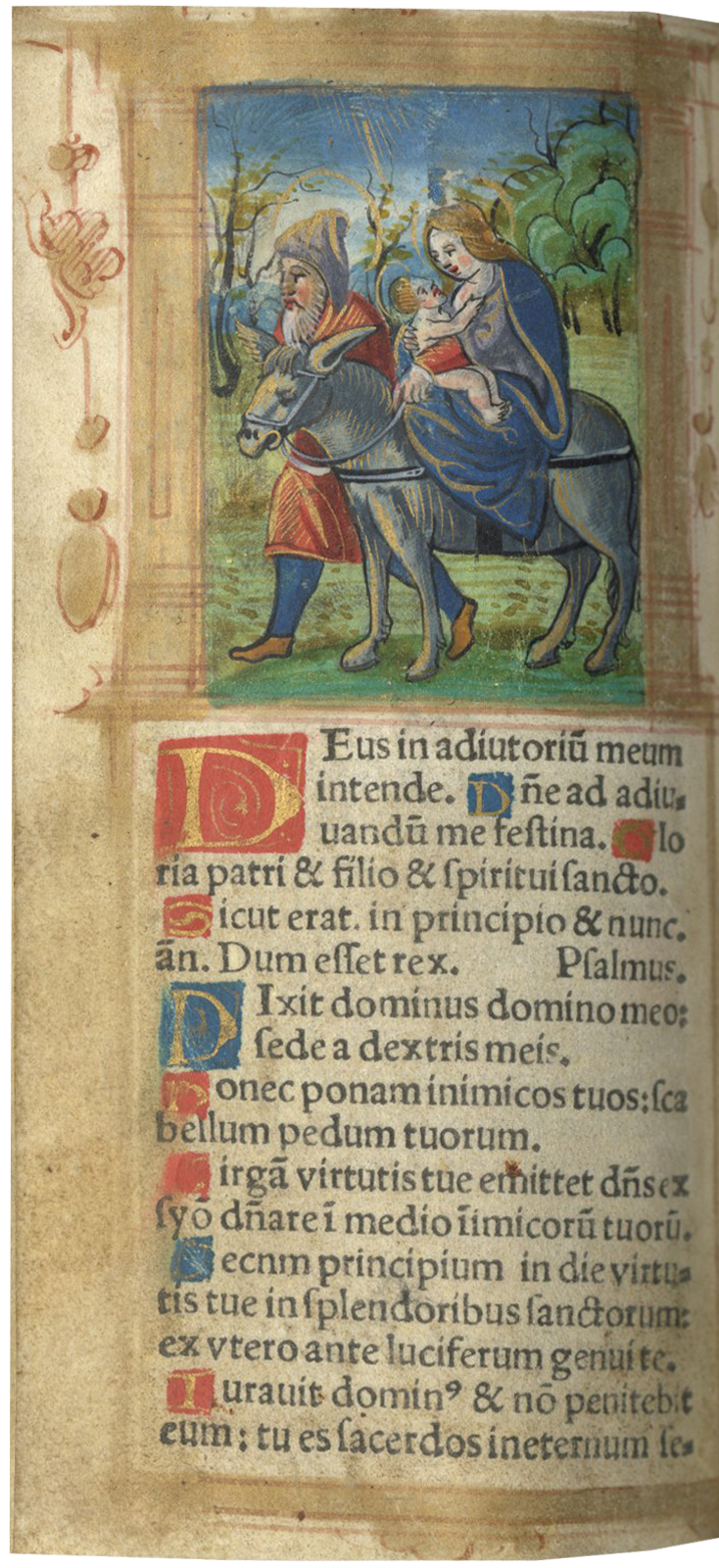

f. 43v, Flight into Egypt;

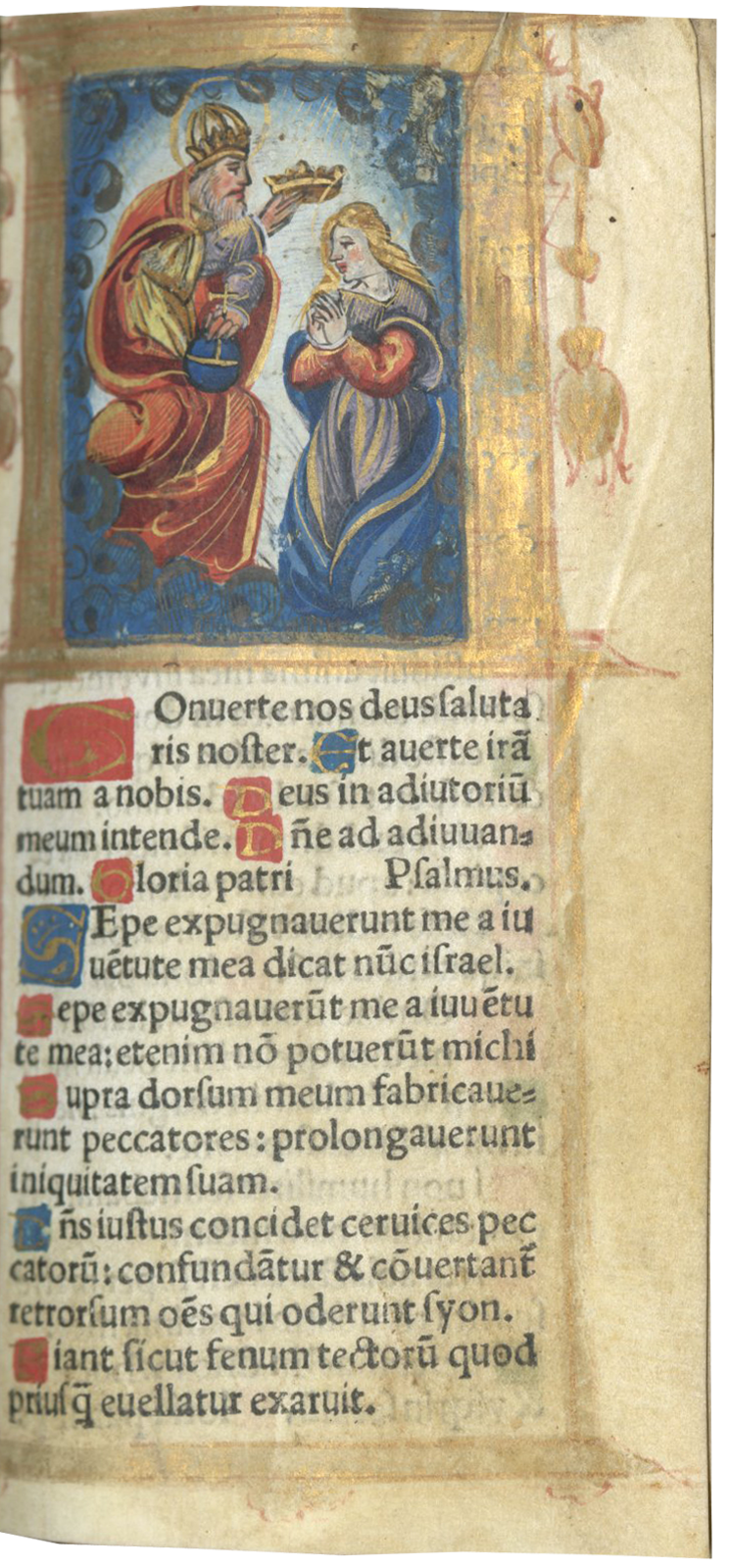

f. 47, Coronation of the Virgin;

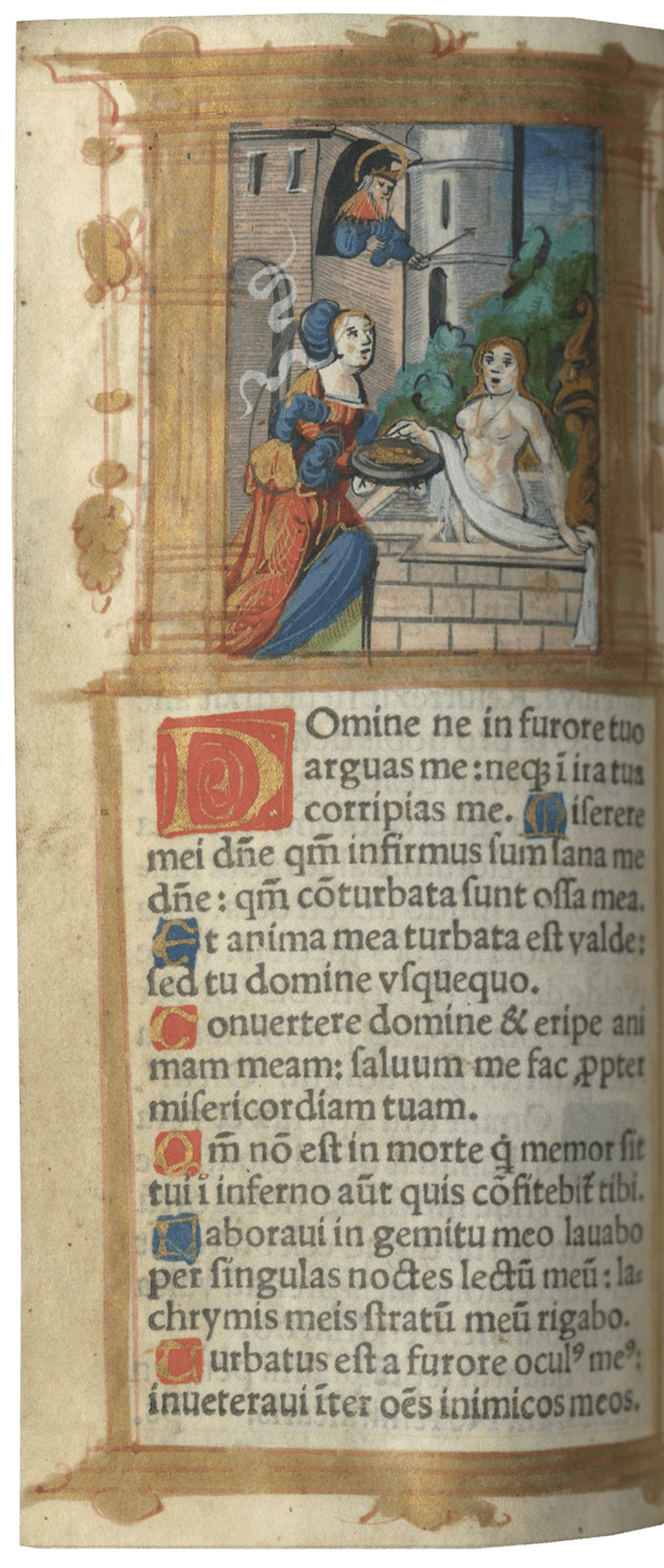

f. 53v, David spies on Bathsheba in her bath with female attendant;

f. 61v, Job seated on a dung heap, witnessed by his wife and friend.

Printed Book of Hours like the present example illustrate the transition between the world of the medieval manuscript and the age of the printed book. In contents, use, and layout they follow in the tradition of the medieval illuminated Book of Hours – lavishly illustrated texts for private prayer that have been called the “best sellers” of the late Middle Ages. Technically, however, such books are the products of print technology. The handwritten script of the past has been simulated with type, and hand-painted miniatures have been replaced by detailed metalcuts that still follow the traditional iconography of the manuscript Book of Hours but add richness and complexity through additional parallel narratives. Other traditional manuscript components, including painted initials, line fillers, and borders on every text page, have been added by hand or replaced by further sets of metalcuts.

Germain Hardouyn (active c.1521–1541), and his brother Gilles Hardouyn (1455–1521) achieved the uncommon distinction of being registered as both printers and illuminators. Their Parisian workshop specialized in over-painted prints (recently called “print-assisted paintings”), with both the printing and illuminating occurring in-house. The Hardouyn workshop received print matrices from other workshops, such as that of Jean Pichore, also an illuminator, who took inspiration from Albrecht Dürer and Martin Schongauer in composing his metalcuts. The illustrations in the present Book of Hours are not derived from the Pichore metalcuts known to have been used by the Hardouyns, though they seem to have been heavily influenced by them. The Hardouyn workshop illuminators were guided by the metalcuts, but also altered their compositions according to their own abilities and tastes. The paintings here are skillfully rendered with shaded modeling and drapery folds, precise gold line highlights, and expressive, rosy-cheeked figures.

The metalcut series of the present book has parallels to a unique Book of Hours printed by Germain Hardouyn, c. 1534 (Tenschert and Nettekoven, 2003, III, no. 147), which is illustrated by a series of miniatures rather than metalcuts. A Book of Hours sold at Sotheby’s, (London, December 7, 2015, lot 21) appears from available images to be very similar to the volume described here, with an almanac from 1534–1536. This is a very rare imprint, not in Lacombe (1907) or Brunet (1860–1865); very likely Moreau-Renouard, 1972–2004, vol. 5, p. 105, no. 194, BP 16 108201, Bohatta, 1924, no. 1177, although no collation is listed, and the imprint is described simply as an octavo, listed in these sources is a single copy sold by L. Rosenthal, Munich, Cat. XXII, no. 4032, no date, 188?, where it is described as bound in modern gold-tooled calf.

Literature

Likely published:

B. Moreau, and P. Renouard, with G. Guilleminot-Chrétien and M. Breazu. Inventaire chronologique des éditions parisiennes du XVIe siècle, Histoire générale de Paris, 5 vols., Paris, 1972–2004. vol. 5, p. 105, no. 194, BP 16 108201.

H. Bohatta, Bibliographie der Livres d’Heures: Horae BMV, Officia, Hortuli Animae, Coronae BMV, Rosaria und Cursus BMV des XV und XVI Jahrhunderts, Vienna, 1924, no. 1177.

Bibliotheca Catholico-Theologica, Catalogue XXVIII de la librairie ancienne de Ludwig Rosenthal, Munich, George Schuh, 188?, no. 4032.

For further literature and comparative examples, see:

M. Warren, “Gillet and Germain Hardouyn’s Print-Assisted Paintings, Prints as Underdrawings in Sixteenth Century French Books of Hours,” in The Reception of the Printed Image in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, Multiplied and Modified, eds. G. Jurkowlaniec and M. Herman. Routledge 2020.

A. Pettegree and M. Walsby, French Books III & IV: Books Published in France Before 1601 in Latin and Languages Other Than French. Leiden: Brill, 2012, no. 67493.

H. Tenschert and I. Nettekoven, Horae B.M.V.: 158 Sundenbuchdrucke der Sammlung Bibermühle, Rotthalmünster, Antiquariat Heribert Tenschert, 2003, III, no. 143.

E. Angermair, J. Koch, A. Löffelmeier, E. Ohlen, and I. Schwab, Die Rosenthals. Der Aufstieg einer jüdischen Antiquarsfamilie zu Weltruhm, Böhlau, 2002.

P. Renouard, Répertoire des imprimeurs parisiens, Paris, 1965, pp. 197–198.

J. Müller, Dictionnaire abrégé des imprimeurs/éditeurs français du XVIe s., Paris, 1970, p. 76.

L.-C. Silvestre, Marques typographiques, ou, Recueil des monogrammes, chiffres, enseignes, emblèmes, devises, rébus et fleurons des libraires et imprimeurs qui ont excercé en France, depuis l'introduction de l'imprimerie, en 1470 …, Paris, 1853, no. 57.

C.-J. Brunet, “Notice sur les Heures Gothiques Imprimées à Paris à la fin du quinzième siècle et dans une partie du seizième,” Manuel du libraire et de l’amateur de livre, Paris 1860-1865, Vol. 5, col. 1553–1684; Hardouyn, cc. 1628–1644.

J. Van Praet, Catalogue de livres imprimés sur vélin, qui se trouvent dans des bibliothèques tant publiques que particulières, pour servir de suite au Catalogue des livres imprimés sur vélin de la Bibliothèque du roi, Paris, 1824.