From Yesteryear to the Present Day: Books of Hours

Text by Sandra Hindman

What was it like to live six or seven hundred years ago?

When you woke up in the morning, how did you know what time it was, what day it was, what month it was?

What was the bedroom you slept in like?

Did you have a sense of the world at large and your place in it? What did you do during the day? Work? Leisure time? There was no television, no streaming platforms, no YouTube, but there were books.

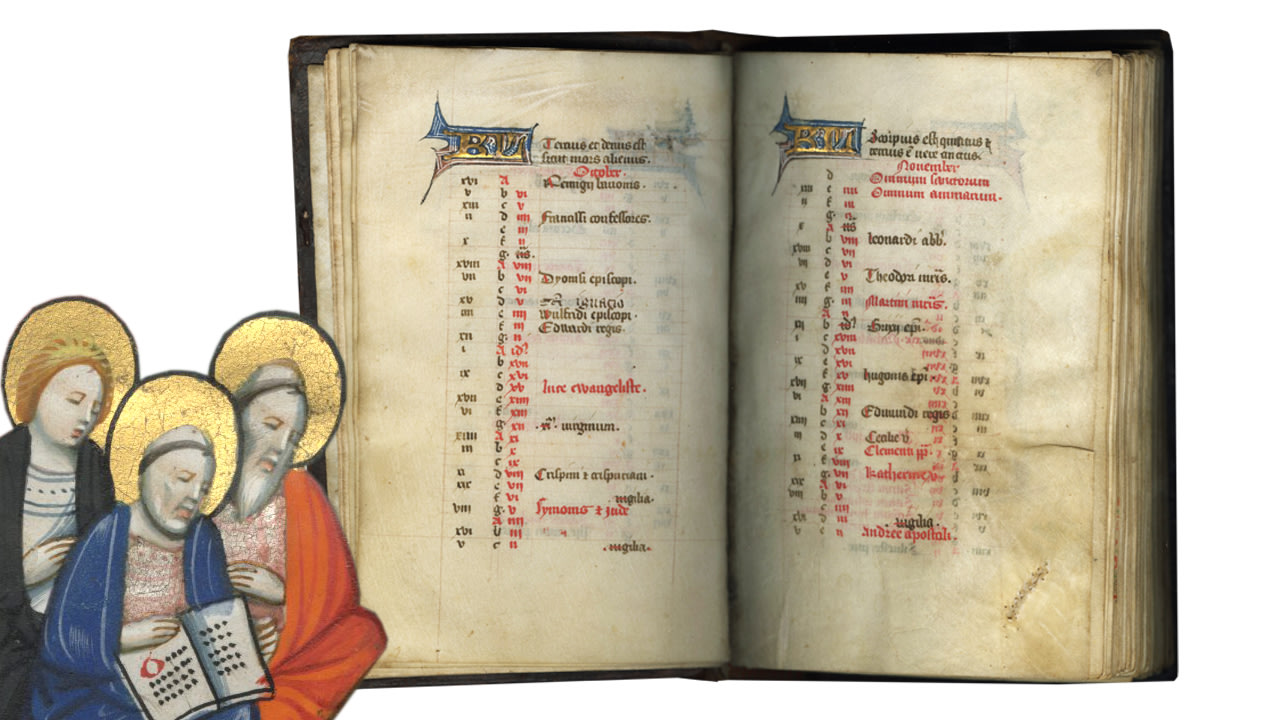

These books were manuscripts, written and illuminated by hand. Books of Hours. I have estimated that one in four families in medieval France owned a Book of Hours in the fifteenth century. These highly personalized manuscripts tell us more about how people lived long ago than almost any other artwork of the Middle Ages. They connect the past to the present – our present. Books of Hours structured time for their readers. They open with a perpetual calendar filled in with the names of saints to be celebrated each day and special holiday.

The special days were indicated in red; they were “red letter days.” You could calculate every day that was movable, Sundays and Easter, for example. At the opening of this Book of Hours, the days for fasting are indicated, as well as the way to calculate Easter and Sundays. We know the book belonged to Clarisse van de Hoeghe, just an ordinary person, married to a leather tanner, who lived in Ghent. A T-O map drawn on these opening pages situated Clarisse in the world.

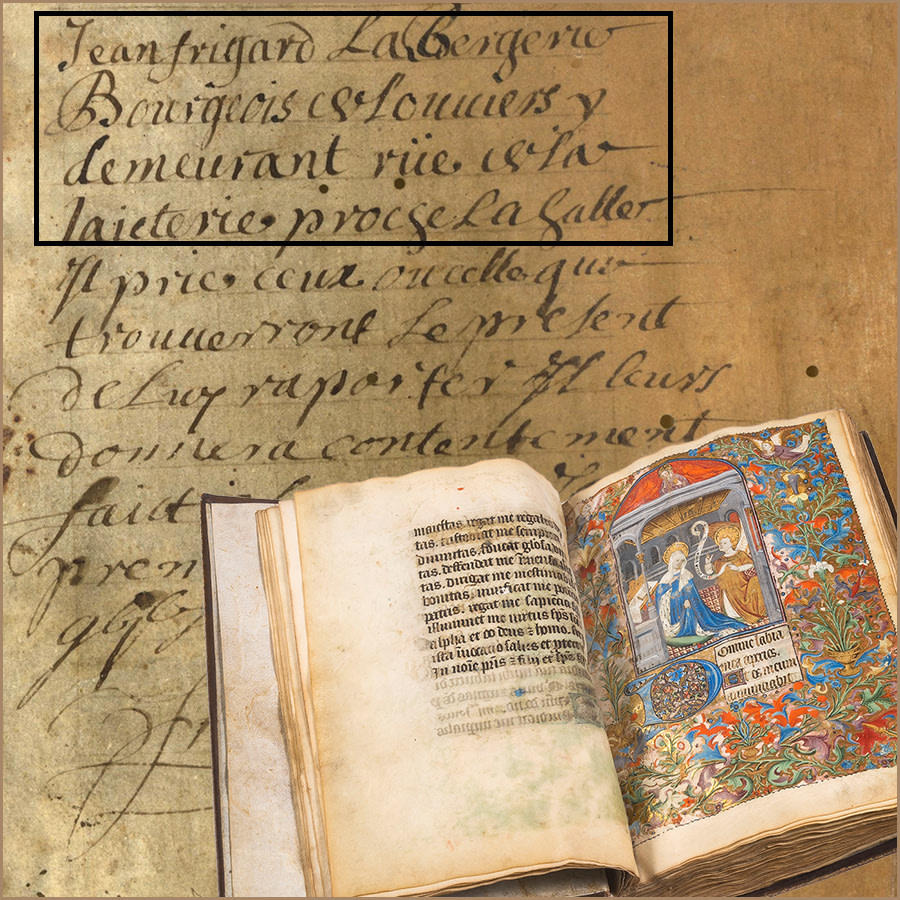

It shows the three continents then known – Europe, Asia, and Africa. Clarisse treasured her book. She wrote her name, her address, and the name of her husband in it. So did Jean Frigard, who went one step further after recording his name and address in his copy and offered a reward to anyone who found his book, if it was lost.

The lives of ordinary people, especially women, unfold in the pages of these Books of Hours. Every woman could identify with the Virgin Mary who learns she will give birth, and each could wistfully dream that an angel, like Gabriel, would bear the news.

In the Annunciation, a picture of Mary opens the sequence of pictures for the Hours of the Virgin, intended to be recited eight times a day from morning to night, marking the times of the day, this prayer before dawn. Mary’s bedroom was appointed with a canopied bed, a nightstand, sometimes a devotional image above the headboard, just like the room of most women. She is shown reading. Her pregnancy, the birth of her child, and other moments during his childhood trace milestones in the lives of a family, any family.

Sometimes the illuminated borders of Books of Hours reveal as much about everyday reality as the main pictures.

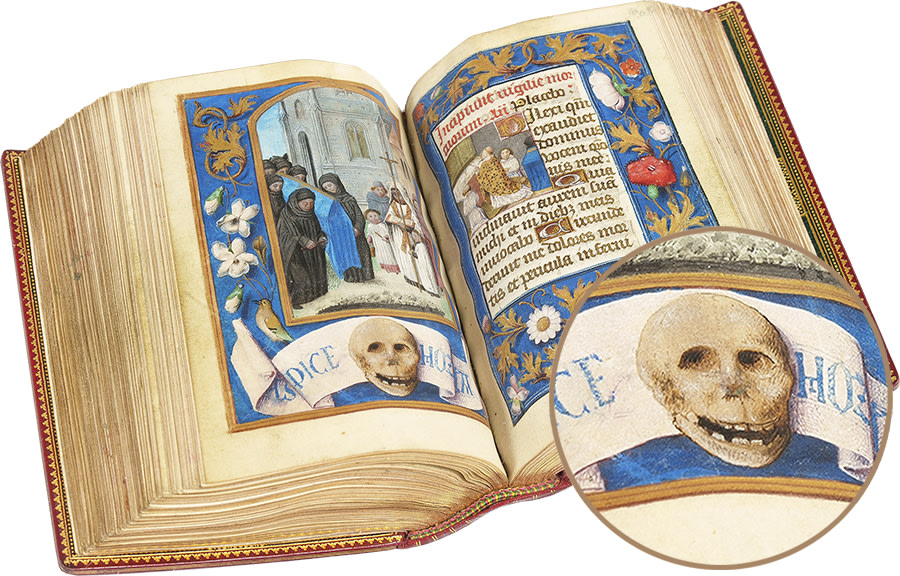

In this one, true-to-life precious pendants, rings, and amulets have spilled out of a jewelry box onto the page. The manuscript belonged to a nun. Her portrait appears in the miniature of the Crucifixion. Could she have left behind these worldly goods upon taking her vows, only to have them, imitated in paint, accompany her in her manuscript? In another Book of Hours the skull in the border is more eloquent than the principal scene of the funeral in the churchyard that accompanies the prayers for the Office of the Dead. In the case of a friend or family member’s funeral, you took your Book of Hours with you as you mourned for the deceased during the service. Such miniatures depict another moment of everyday life.

Within the pages of an intimate, hand-held Book of Hours, the outside world bursts into our own space – townscapes, the countryside, churches, castles. The Flight into Egypt takes place in the countryside in front of a traveler’s inn, adorned with shields of various towns.

King David leers at Bathsheba naked in her bath in the courtyard of a lavish castle. He prays to God for forgiveness in a barren rocky landscape, dotted in the background with towers. The floral borders, sometimes full of potted plants, are symbolic. They also promise the bountiful, sunny days of Spring and Summer.

The pages of Books of Hours reveal a world of yesteryear. Clarisse, Jean Frigard, the anonymous nun, Johannes Merkis, Richard Newton – their experiences, their manuscripts and the pictures in them, provide a thread that connects the past to the present. Today we read books, we watch movies, partly for entertainment. But these vicarious activities help us better understand other people and different situations. They divulge a range of human experience that aids in grounding our own existence in the present. So too with Books of Hours.