The Earl of Ashburnham Songe du Vergier

The Earl of Ashburnham “Songe du Vergier”

, France, Lyons, c. 1455-1460

The Earl of Ashburnham “Songe du Vergier”

Description

The rediscovery of this important illuminated manuscript, whose whereabouts have been unknown for more than a half century, is noteworthy. Of royal provenance, its text preserves an allegorical political treatise written in a lively vernacular from the era of the Wise King Charles V. Its illumination is securely attributed to the Master of the Roman de la Rose of Vienna, a skilled and influential illuminator working in Lyons for royal and noble patrons in the mid-15th century under the reign of Charles VII (r. 1422-1461). The two large miniatures demonstrate both the narrative ambition and masterful craftsmanship of this artist. In pristine condition and in a magnificent 18th-century binding, the majestic manuscript boasts an almost continuous provenance through many eminent collections.

ii (paper) + 242 + ii (paper) folios on parchment, modern foliation in brown ink in the lower outer corner of some leaves (100, 150, 160, 200, 243, with errors), modern foliation in pencil, 1-242, complete (collation i1 ii4 iii-xxi8 xxii4 xxiii-xxxii8 xxxiii1), horizontal catchwords in the middle of the lower margins on the verso often enclosed within decorative cartouches, ruled in red ink (justification 251 x 167 mm.), written in dark brown ink in Gothic cursive bookhand in two columns on 32 lines, rubrics and underlining in red, capitals touched in yellow, pieds-de-mouches alternating in red and blue, ascenders on the first line of text often decorated with very fine pen flourishes forming detailed human faces, fleurs de lys and spiraling cartouches containing inscriptions, touched in yellow and occasionally red, some pen flourishes decorating the last line of text, 2-line initials in burnished gold on parti-colored grounds in blue and dark pink with white penwork for each of the 468 chapters, Books I and II (ff. 6, 162) begin respectively with a 5-line initial and a 6-line initial in blue with white penwork decoration, infilled with ivy vines in blue and red, on burnished gold grounds, and two large miniatures in gold and colors (155 x 170 mm.) framed by a gold band, within borders made of burnished gold bands decorated with ivy vines and rich rinceaux in the outer margins enlivened with flowers and foliage in vases and pots, and two coats of arms, slight smudging of ink in the rinceaux border on f. 6, a small bit of parchment lacking from the margin in the inner upper corner of f. 182, in overall pristine condition. Magnificent late seventeenth-century binding attributed to Luc-Antoine Boyet (c. 1658-1733) in red morocco, richly gold-tooled with small tools in “plein or” style, both covers with a double frame of berry vines and lilies, spine with six raised bands, gold-tooled with flowers and foliage, gilded title “Songe du Vergier / MSS,” gilt edges, marbled pastedowns and flyleaves, modern fireproof case by H. Zucker in red morocco with gilded title on the spine “Songe du Vergier / Manuscript on vellum / circa 1460”, in excellent condition. Dimensions 381 x 258 mm.

Provenance

1. The manuscript was illuminated around 1455-1460 in Lyons, as suggested by the style of the illumination, script, and contextual evidence. The earliest mark of ownership is the autograph signature of Françoise d’Alençon (1490-1550), the grandmother of King Henry IV of France, found at the end of the text: “Francoyse dalaison” (f. 240v). The two coats of arms included in the manuscript were added later in the sixteenth or early seventeenth century. Their placement at the top of the leaf is unusual and the original artist left no space in the borders for coats of arms. The Montmorency-Laval arms (d’or à la croix de gueules cantonnée de seize alérions d’azur chargée de cinq coquilles d’argent) on f. 162 at the beginning of Book II were partially painted over the decoration of foliage and flowers. According to Michel Pastoureau and Laurent Hablot, both coats of arms can be dated to the sixteenth century or early seventeenth century by their drawing, visible in the arms on f. 6 especially in the form of the helmet, lambrequins and the rounded bottom of the shield (d’azur à la croix en cordelière à noeuds accompagnée de six étoiles en or). The arms on f. 6 appear to be fictive and cannot be identified. It is uncertain whether the manuscript was ever owned by the Montmorency-Laval family (see below).

2. The signed initials “JB”, dating from the last third of the sixteenth century, are found under the signature of Françoise d’Alençon.

3. From Françoise d’Alençon the manuscript passed to her grandson, King Henry IV of France (1553-1610).

4. On 27 November 1601, the manuscript was given to Claude Chrestien, the son of Florent Chrestien, poet and librarian of Henry IV. The manuscript inscription recording the gift by a certain J. M., lord L. G. is found on f. 1: “En perpétuelle mémoire de franche et liberale volonté jay baillé pour jamais ce présent livre à mon feal et meilleur amy Claude Chrestien, fils de Monsieur Florent. J. M. sr de L. G. le xxvie novembre 1601.”

5. An inscription at the top of f. 241 indicates a price paid for the manuscript, datable to the second half of the seventeenth century: “Pour la somme de 80 (or 10) lb.”

6. Georg Wilhelm, Freiherr von Hohendorf (c. 1670-1719), Austrian general, Adjutant-General of Prince Eugene of Savoy; “Hohendorf. 40.” inscribed in pencil on the verso of the first front flyleaf; the manuscript is described in the sale catalogue of his library with the current red morocco binding, Bibliotheca Hohendorfiana, ou Catalogue de la Bibliothèque de feu Monsieur George Guillaume Baron de Hohendorf..., The Hague, 1720, p. 237, no. 40.

7. Henry Drury (1778-1841), master at Harrow and a close friend of Lord Byron; his autograph note is at the top of the second front flyleaf; sold at his sale in London by Robert Harding Evans: Library of the Rev. Henry Drury, M.A., late fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and Rector of the Fingest, Bucks, F.R.S.F.S.A., 19 February 1827, no. 4074; sold to Hibbert.

8. George Hibbert (1757-1837); at his sale in 1829, no. 7584; sold to Bohn (is this the bookseller Henry George Bohn, 1796-1884, who began his career as a dealer in 1831?).

9. P. A. Hanrott; a long autograph note on the second front flyleaf; sold in London by Evans: Catalogue of the Splendid, Choice, and Curious Library of P. A. Hanrott, esq. ... sold by auction, by Mr. Evans, 1834, part iv,p. 37, no. 712.

10. Joseph Barrois (1780-1855); the manuscript makes part of the collection he sold in 1849 to Earl of Ashburnham (see below).

11. Bertram Ashburnham (1797-1878), 4th Earl of Ashburnham (Ashburnham Place, Sussex); Catalogue of the Manuscripts at Ashburnham Place, part the second comprising a collection formed by Mons. J. Barrois, London, 1861, The Barrois manuscripts, no. 108; the collection was inherited by his son, Bertram Ashburnham (1840-1913), 5th Earl of Ashburnham.

12. Clarence S. Bement (1843-1923), the American collector, whose armorial bookplate is pasted inside the front pastedown.

13. Gabriel Wells (1861-1946), bookseller in New York.

14. In the library of John B. Stetson Jr. (1884-1952), the American diplomat, businessman and book collector; sold at American Art Association, Anderson Galleries, New York, on 17 April 1935, Romances of Chivalry, European Literature, French Books with Engravings & Rare Americana from the Library of John B. Stetson,no. 150.

15. Bookseller William Kündig, Geneva.

16. Bookseller in Brussels before 1952 (cf. Mourin 1952, p. 96).

17. Bookseller Nicolas Rauch S. A., Geneva, sold on 12 May 1952, New series, cat. no. 1.

18. Bookseller Lardanchet, Paris, 1953, catalogue 47, no. 2329, in 1955, catalogue 49, no. 3378, and again in 1956, catalogue 50, no. 3861.

19. Private Collection, France.

Text

f. 1r-v, ruled, otherwise blank;

ff. 2-5v, list of rubrics (according to Louis Mourin, our manuscript is the only copy to include this list of contents, cf. Mourin, 1952, p. 100), incipit, “Icy s’ensuivent les rubriches de se present livre appellé le songe du vergier... Item veoir si la vierge marie fut concevé en peche originel ou non”;

ff. 6-240v, [Évrart de Trémaugon, Songe du Vergier],incipit, “Audite sompnium meum quod vidi. Ces parolles sont escriptes genesis .xxxviii°. capitulo... et super parentes vestros et filios filiorum vestrorum usque in terciam et quartam generacionem, et sit semen vestrum benedictum a Domino Deo Israel, qui regnat in secula seculorum. Amen. Cy finist le livre du songe du vergier”;

Edited by Marion Schnerb-Lièvre (Paris, 1982; edition based on the original offered to Charles V, London, British Library, Royal MS 19 C. IV); ff. 6-160, Book I; f. 160v, ruled, otherwise blank; f. 160r-v, blank, no ruling; ff. 162-240v, Book II.

ff. 241-242v, ruled, otherwise blank.

The Songe du Vergier (or Verger; Dream of the Orchard) is an anonymous political treatise composed on the request of King Charles V of France, and first completed in Latin under the title Somnium Viridarii in 1376. Two years later, in 1378, it appeared as a revised, livelier version in French. The original dedication copy of the French version, including the king’s autograph note, survives in the British Library, Royal MS 19 C. IV (fully digitized, see Online Resources). All other known medieval copies, in Latin and French, date from the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The revival and success of the Songe at the end of the Middle Ages is also attested by editions printed in Lyon in 1491 and in Paris in 1499, 1516 and 1530. There are excellent modern editions of both the Songe and the Somnium by Marion Schnerb-Lièvre (Paris, 1982 and 1993). Her arguments showing that the Breton jurist and royal servant, Évrart de Trémaugon, is the author of both the Latin and French texts are now generally accepted; the Latin text served as a draft for the author from which he profoundly reorganized and improved the work (cf. Schnerb-Lièvre, 1980, 1982, 1992, and others). The style of the Songe is especially elegant with several words used in French for the first time or with a new meaning (Schnerb-Lièvre, 1992).

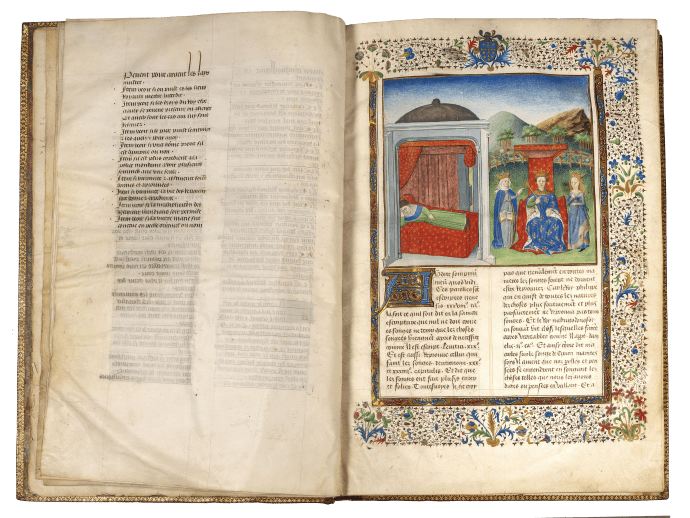

The prologue, addressed to Charles V, explains the narrative presented in the framework of a dream, a form of narrative popular since the Roman de la Rose in the thirteenth century. The author falls asleep in an orchard, and the king, accompanied by allegorical representations of the Spiritual and the Secular Power (shown as two crowned women in the miniature), appears to him in a dream, each with her chosen advocate, the Cleric and the Knight, who debate disputed points. The work is organized as a long dialogue between the Cleric and the Knight, providing the first official somme on the relations of the ecclesiastic and secular powers, and more specifically, the functions of the pope and the king of France at the end of the fourteenth century. Despite an apparent impartiality, it lays out a strong defense in favor of the royal politic. The discussion is composed of 468 arguments from the advocates, divided into two books, on subjects such as the ethics of political power, tyranny (Book I, ch. 131-132), the education of princes (I, ch. 133-134), taxation (I, ch. 135-136), the choice of advisers (I, ch. 137-138, 186), the return of the pope to Rome (I, ch. 155-156), the pretentions of the English kings to the crown of France (I, ch. 141-142), the matter of Brittany (I, ch. 143-144), the origin of the nobility (I, ch. 149-154), celibacy and marriage (II, ch. 256-260), and the right to war (I, ch. 154-155). In the epilogue the author awakens and presents his work to the king.

The vernacular Songe was much more widespread than the Latin Somnium (eight copies known), and was generally preferred by princes and other laymen, while the Somnium was owned by university men. Twenty-one copies of the Songe are preserved in public collections, all in libraries in Europe, except for the copy made for Pierre II d’Urfé, grand écuyer de France for Charles VIII, now in Saint Petersburg (cf. Jonas, Online Resources; in addition to 21 copies, there are 6 fragments, including two leaves from the epilogue sold at Les Enluminures, TM 284, now University of California, Rouse MS 108). In addition to our manuscript, nine manuscripts, now lost, are known from the inventories of Jean d’Orléans (d. 1467), count of Angoulême (and later in the possession of his son Charles d’Orléans, d. 1496), Jean d’Orléans (d. 1468), count of Dunois (“bâtard d’Orléans”; his copy was bound in green velvet), Philip the Good (d. 1467), duke of Burgundy (the binding decorated with Philip’s badge in silver), the dukes of Bourbon (at Aigueperse in 1507), the Abbey of Saint-Sulpice in Bourges, the Augustinian convent of Croix-Rousse in Lyon (ms. 186), the convent of Saint-Bonaventure in Lyon, and the collections of Duke of La Vallière (d. 1780) and Sir Thomas Phillipps (d. 1872; no. 2288) (cf. Jonas, Arlima, Stratford 2006).

Who commissioned our manuscript? It was made at the end of the Hundred Years’ War, soon after Charles VII’s definitive defeat of the English in 1453. It belongs to a small group of copies made at this time for great military leaders, such as Jean d’Angoulême and Jean de Dunois, who had helped Charles VII liberate the French kingdom from the English. The revival of the text in the 1450s was clearly intended to inspire the princes and great nobles around Charles VII to define French identity and construct a strong nation. Jean d’Angoulême, for instance, owned two copies, one of which was written for him at La Rochelle in 1452/3 by Guillaume Arbalestier (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Fr. 537; cf. Schnerb-Lièvre, 1982, pp. xxiv-xxv; see Online Resources). Another copy was painted by the Master of Étienne Sauderat in Paris in the 1450s for Jean du Mas (c. 1437-1495), lord of l’Isle-sur-Arnon (Berry) and écuyer of Charles, Duke of Orléans (and later of Pierre de Bourbon); incidentally, this manuscript later belonged to the Montmorency-Laval family (Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 220; see Online Resources).

How did the manuscript come into the hands of Françoise d’Alençon (1490-1550)? Although she wrote her name in it, the work was clearly made for and owned by men. Françoise d’Alençon had married Charles de Bourbon (1489-1537), count of Vendôme, the grandson of Jean VIII de Bourbon (1425-1478), count of Vendôme, who fought the English in Normandy and Guyenne at the end of the Hundred Years’ War. Was the manuscript made for Jean VIII de Bourbon? Notably, Jean was the son of Louis de Bourbon (1376-1446) and Jeanne de Laval. If the manuscript was made for a member of the Montmorency-Laval family, the most likely candidate is Jeanne’s brother, Guy XIV de Laval (1406-1486), who had distinguished himself in the Hundred Years’ War and was counted almost as family by Charles VII. If the manuscript was not passed down in the Bourbon family, it could have arrived in the hands of Françoise d’Alençon from Guy XV de Laval (1486-1501; Guy XIV’s son) and his wife Catherine d’Alençon (1452-1505; Françoise’s aunt), who died without children, as was suggested by Louis Mourin (Mourin, 1952, p. 97).

Although the Montmorency-Laval arms were added to our manuscript afterwards, it is worth considering the possibility that Guy XIV de Laval commissioned it, and that the added arms are commemorative. His parents, Jean de Montfort (Guy XIII de Laval) and Anne de Montmorency-Laval (the heir of Guy XII), had two daughters, Jeanne and Catherine, and three sons, François de Laval who was heir to his father, becoming Guy XIV, André de Lohéac (1408-1486) and Louis de Laval-Châtillon (1411-1489). The arms of the second son, André, include a label: un lambel trois pendants d’argent; sur chaque pendant une pointe d’hermine (cf. Armorial de Gilles le Bouvier, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 4985,f. 19v; a label is also included in his arms reproduced in Paris, BNF, MS fr. 611, f. 3 (with errors to the color and charge of the label)). The label, which is not present in the arms painted in our manuscript, was used to distinguish André’s arms from those of his elder brother, Guy XIV, who used the arms of his father after the premature death of his father in 1414, when Guy XIV was only eight years old (Jean de Montfort had taken the arms of his wife, as stipulated in the marriage contract).

The youngest son, Louis de Laval, would become a great bibliophile, commissioning, amongst others, a remarkable Book of Hours (Paris, BNF, MS lat. 920) and a magnificent history of the crusades, Les Passages d’Outremer, written by his secretary, Sébastian Mamerot (Paris, BNF, MS fr. 5594). However, these commissions date from the 1470s, and in the 1450s Louis de Laval was occupied as the governor of Dauphiné and subsequently of the city of Genoa.

There is also a possibility that the choice to place the Montmorency-Laval arms directly above the miniature depicting the Knight (rather than in the lower margin of the opening leaf, as was more common) was meant to suggest a portrayal of the patron as the Knight advocating for the Secular Power, and the sovereignty of the king. (It is not a true portrait, the face of the Knight is generic, as was typical for this artist; cf. the portrait of Guy XIV’s brother André de Lohéac, painted around the same time by the same artist in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS fr. 4985,f. 19v.) The fictive arms with the cordelière on f. 6 may by contrast represent the Cleric.

Guy XIV distinguished himself in battle fighting alongside Joan of Arc in the Loire campaign against the English in 1429. Charles VII rewarded him by raising the lordship of Laval to the rank of a county, and included him among the six peers who took part in his coronation at Reims in 1429. Guy XIV married the daughter of the duke of Brittany and was often asked to mediate between the king and the duke. In 1472 he was made lieutenant-general of Brittany, and shortly before his death, Grand Master of France (head of the king’s household) for Charles VIII. Incidentally, the first husband of Guy’s grandmother, Jeanne de Laval, was Bertrand du Guesclin (c. 1320-1380), who in turn had helped Charles V to liberate most of the French kingdom from English occupation. Although there is no contemporary evidence that he was the patron of our manuscript, his profile presents a strong candidacy until further proof is found.

Illumination

Two large miniatures:

f. 6, The Author asleep; King Charles V between allegories of the Spiritual and Secular Power;

f. 162, Argument of the Cleric and the Knight.

In 1983, John Plummer attributed the decoration of the Songe du Vergier to the illuminator of a Livre du roy Modus et de la Reine Ratio (New York, Morgan Library and Museum, MS M.820; fig. 1). Plummer assumed that the artist had been active in Brittany or Anjou in order to account for his stylistic ties with the Jouvenel Master and André de Laval’s alleged patronage as admiral and marshal of France (Plummer 1983, pp. 34–35, no. 46). In 1993, François Avril named this anonymous artist after a volume of the Roman de la Rose in Vienna (ÖNB, Cod. 2568) and gathered an ensemble of no less than fifteen manuscripts for the most part in public collections (Avril and Reynaud 1993, pp. 199–201). A consideration of the liturgical use of these manuscripts led him to relocate his activity from Western France to Lyons. The artist’s prestigious clientele, ranging from royal courtiers to members of the local high clergy, demonstrates his success in this economic capital of the realm, second only to Paris at the time.

In 1993, François Avril deemed that the decoration of the present manuscript belonged to the middle phase of the Master of the Vienna Roman de la Rose’s career, around 1450. The author related its illumination to that of the Livre du roy Modus et de la Reine Ratio (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS M.820) and to two other volumes of Alain Chartier’s works (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 2265; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, MS 78 C 7). The frontispiece miniature (f. 6) of the present manuscript is similar to that of a volume of Laurent de Premierfait’s Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes, copied in Bourges in 1437 for Jean Paumier, a royal tax collector appointed in Lyon in 1433 (Paris, BNF, MS fr. 229, f. 1; fig. 2). A monumental ambition defines the composition of both miniatures, balancing the image of the author within an architecture on the left side with an outdoor scene on the right side, developed before a receding landscape of rounded hills, punctuated with groves of tiny trees. Further analogies include the stiff attitudes and demonstrative gestures of Boccaccio and Cavalcanti on the one side, of the cleric and knight on the other. A subtle yet vigorous modeling of the faces and rounded foreheads, consistent with the rest of the Master of the Vienna Roman de la Rose’s production, defines these stocky figures. Further, the enthroned image of Charles V relates to a series of royal portraits, among which the closest examples are those of the Livre du roy Modus et de la reine Ratio (see e.g. f. 2v, 121; fig. 1).

The second miniature depicting the Argument of the Cleric and Knight (f. 162) offers one of the finest examples of the artist’s mastery as a draftsman. The characters are set within an uncluttered interior space that extends outside the miniature. The architecture vigorously shadowed with short diagonal black lines and the decorum restrained to motifs of slim lancets are identically found in a contemporary volume of Alain Chartier’s works (Paris, BNF, MS fr. 2265; fig. 3). In the foreground of our miniature stand the cleric and the knight, draped in rich velvet garments. Their colors achieve a harmonious balance, highlighted only by the discreet yet vivid contrast of the knight’s red collar with his blue doublet lined with fur. An even greater subtlety characterizes the firm modeling of the faces, fingers, hands, and drapery folds, for it relies mostly on the short diagonal hatching and thin outline in brown ink applied at a preliminary stage. The consistency and refinement of the artist’s personal style and technique in the decoration of this manuscript is demonstrated upon comparison with the debate of Boccaccio and Petrarch in Jean Paumier’s volume (Paris, BNF, MS fr. 229, f. 303v; fig. 4).

The Master of the Vienna Roman de la Rose is considered as the most important and influential artist active in Lyon under the reign of Charles VII (r. 1422-1461). That he was also a painter is suggested by echoes of his style in the very few remnants of mid-fifteenth century monumental painting in Lyon, such as the civil window of the Chess Players in the Musée de Cluny (fig. 5), and the Musician Angels of the church of St. Paul, Lyon. It has been suggested albeit without evidence that he could be identified with Jean Hortart, a painter, illuminator, glazer, and embroiderer of Scottish origin documented in Lyon from 1412 to 1465 (Elsig 2007, pp. 89-90). Recent contributions have discussed the possibility that the Master of the Vienna Roman de la Rose would have begun his career in Bourges in the wake of the Master of Marguerite of Orléans, which would account for the fact that his early manuscripts were commissioned by members of the royal court exiled in the city (Seidel 2017, pp. 185-193; Castaño 2018).

In her recent monograph on the artist in 2022, Mireia Castaño includes this manuscript among the literary works illuminated by the Master of the Roman de la Rose of Vienna as “location unknown” (cat. 24). She underscores the similarities with the Alain Chartier manuscript in Paris (MS fr. 2265) and dates our copy 1455-1460 based on its relationship to the Paris manuscript.

Literature

Published:

Avril, F. and N. Reynaud. Les Manuscrits à peintures en France, 1440-1520, Paris, 1993, cited p. 200.

Castaño, M. Le Maître du Roman de la Rose de Vienne Silvana Editoriale, 2022, pp. 82-83, cat. 24.

Mourin, L. “Le manuscrit ex-bement du Songe du verger,” Scriptorium: Revue internationale des études relative aux manuscrits 6 (1952), pp. 95-102.

Piazza, G.M. and A. Dillon Bussi (ed.), La biblioteca Trivulziana, Fiesole, 1995, notice, p. 95 by S. Pettenati.

Plummer, J. assisted by G. Clark. The Last Flowering: French Paintings in Manuscripts, 1420-1530, from American Collections, New York, 1982, cited p. 35.

And online

“Evrart de Tremaugon” in ARLIMA (citing this manuscript as no. 25, location unknown)

https://www.arlima.net/eh/evrart_de_tremaugon.html

Further reading:

Autrand, F. and P. Contamine. “Les livres des hommes de pouvoir: de la pratique à la culture écrite,” Pratiques de la culture écrite en France au XVe siècle. Actes du Colloque international du CNRS. Paris, 16-18 mai 1992., Textes et Etudes du Moyen Age 2, Louvain-la-Neuve, 1995, pp. 193-215.

Castaño, M. “Le Maître du Roman de la Rose de Vienne et sa clientèle à Bourges,“ in Peindre à Bourges aux XVe-XVIe siècles, ed. F. Elsig, Milan, 2018, pp.

Combettes, B. “La réfutation dans le texte argumentatif en moyen français: faits syntaxiques et opérations textuelles,” Le Moyen français, 33 (1993), pp. 7-19.

Conihout, I. de and P. Ract-Madoux, Reliures françaises du XVIIe siècle: Chefs-d'oeuvre du musée Condé, Paris, 2002, pp. 64-110.

Coville, A. Évrart de Trémaugon et le “Songe du verger”, Paris, 1933.

Elsig, F. “Dossier lyonnais,“ in Quand la peinture était dans les livres. Mélanges en l’honneur de François Avril, ed. M. Hofmann and C. Zöhl, Turnhout, 2007, pp. 89-97.

Fronska, J. “139. Le Songe du Vergier,” Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination, S. McKendrick, J. Lowden, K. Doyle, J. Fronska and D. Jackson, London, 2011,pp. 392-393.

Lagarde, G. de. Le Songe du Verger et les origines du gallicanisme, Thouars, 1934.

Lewis, P. S. “War Propaganda and Historiography in Fifteenth-Century France and England,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 15 (1965), pp. 1-21.

(For a number of fragments of the Songe at the British Library and the Bodleian, see p. 4, n. 4.)

Mombello, G. “Reflets de la culture française dans l'oeuvre d'un juriste astesan du début du XVIe siècle: la Sylvia nuptialis de Giovanni Nevizzano,” Et c'est la fin pour quoy nous sommes ensemble. Littérature, histoire et langue du Moyen Age. Hommage à Jean Dufournet, Paris, 1993, pp. 991-1008.

Müller, K. “Über das Somnium viridarii,” Zeitschrift für Kirchenrecht 14 (1877), pp. 134-205.

Quillet, J. La philosophie politique du Songe du Vergier (1378): Sources doctrinales, Paris, 1977.

Quillet, J. “Quelques aspects de la perception du juridique au Moyen Age. L'exemple du Songe du Vergier,” Le Droit et sa perception dans la littérature et les mentalités médiévales. Actes du Colloque du Centre d'Ét. Médiévales de l'Univ. de Picardie, Amiens 17-19 mars 1989, Göppingen, 1993, pp. 155-166.

Royer, J. P. L’Église et le royaume de France au XIVe siècle d’après le Songe du Vergier et la jurisprudence du Parlement, Paris, 1969.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. “Evrard de Trémaugon et le Songe du Vergier,” Romania 101 (1980), pp. 527-530.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. Le Songe du Vergier: édité d'après le manuscrit Royal 19 C IV de la British Library, 2 vols, Sources d'histoire médiévale, Paris, 1982.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. “L'auteur du Somnium viridarii en est-il le traducteur?,” Revue du Moyen Âge latin 42:1-2 (1986), pp. 37-40.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. and G. Giordanengo. “Le Songe du Vergier et le Traité des Dignités de Bartole, source des chapitres sur la noblesse,” Romania 110 (1989), pp. 181-232.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. “Nicole Oresme et le Songe du Vergier,” Romania 113 (1992), pp. 545-553.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. “Songe du Vergier,” Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: le Moyen Âge, edited by G. Hasenohr and M. Zink, Paris, 1992, pp. 1402-1403.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. Somnium Viridarii, Sources d'Histoire Médiévale IRHT, Paris, 1993.

Schnerb-Lièvre, M. “Évrart de Tremaugon,” Histoire littéraire de la France, 42, Paris, 2002, pp. 281-296.

Seidel, C. Zwischen Tradition und Innovation. Die Anfänge des Buchmalers Jean Colombe und die Kunst in Bourges zur Zeit Karls VII. von Frankreich, Simbach am Inn, 2017.

Stratford, J. “The Illustration of the ‘Songe du Vergier’ and some fifteenth-century manuscripts,” Patrons, authors and workshops. Books and book production in Paris around 1400, Louvain, 2006, pp. 473-488.

Trémaugon, Évrart de. Trois leçons sur les Décrétales, ed. by M. Schnerb-Lièvre and G. Giodanengo, Paris, 1998.

Online Resources

“Songe de verger” in JONAS (IRHT)

https://jonas.irht.cnrs.fr/consulter/oeuvre/detail_oeuvre.php?oeuvre=9713

London, British Library, Royal MS 19 C. IV

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=royal_ms_19_c_iv_fs001r

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS fr. 537 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8530344b

Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 220

https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/mirador/index.php?manifest=https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/iiif/284/manifest