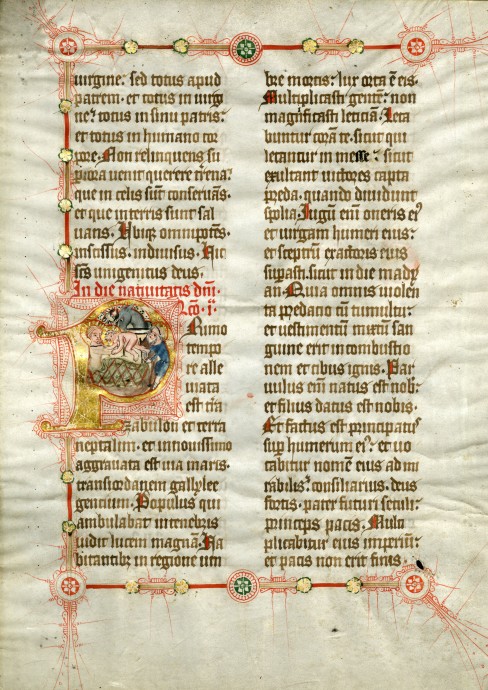

The Nativity in a historiated initial P

Anonymous

, ca. 1340-60Anonymous

Description

Probably from an illuminated Lectionary, the present leaf shows a seven-line historiated initial with the Nativity to introduce the first lection of the liturgy of Christmas. The colors of the washes in the initial are very subdued but harmonious. The red contours of the figures align the vivid scene with the red penwork and red outline of the body of the initial that is given in chased burnished gold. Although with some flaking, the gold initial still reveals the skilful craftsmanship of its makers. It seems that the layer of goldleaf is extremely thin and did not adhere to the grounding very well, which sadly now has affected St Joseph's halo in particular. The surrounding red penwork is very delicate and refined, as is the three-sided bar that frames the text with interspersed little round flower- and ornamental discs or medallions. While both the secondary decoration and the script appear very neat and accurate, thus speaking of very experienced hands, the figures of the Nativity-scene look a bit sketchy and archaic, which, however, is only true at first sight. The scene is dominated by Mary sitting upright in her bed and holding the naked baby Jesus in front of her. The body of the infant, who vividly stretches his right leg in mid-air, spans the length of the bed, so that Joseph, standing at the other end of the bed, can carefully hold onto one foot of the child. A tender fatherly gesture, which is rarely seen in depictions of the Nativity. The figure of Joseph in his blue gown is half inside the initial and half in front of it, as is Mary with her big shining halo. Thus, both figures connect the space of the page and the illusionistic space of the scene “behind” the parchment. The pale green blanket covering the virgin in her childbed is decorated with a plain and characteristic red and white diamond pattern that does not take into account any perspective or folds in the cloth. The heads of the ox and the donkey are partly hidden behind the haloes of Jesus and Mary, but can be detected in the upper arch of the initial, feeding from the crib behind the bed. The pale palette and the bold contours for the figures executed with a brush rather than a pen, evoke an effect of washes, which contrasts the accurateness of the penwork and the script on the page. Although the proportions of the figures' bodies may not appear very balanced, their faces are very expressive with skilful brushstrokes indicating their eyes, brows, noses and mouths.

The leaf, written in two columns ruled in blind tooled double lines for 26 lines, contains the first and second lections for the day of Nativity according to the Ordo Romanum, thus Isaiah 9,1 following and Isaiah 40, 1 following (on the verso). The prickings are still visible on the left, so the page can be considered to be untrimmed. The next leaf of the parent manuscript would most likely have started with the third lection “Consurge, consurge,” Isaiah 52,1 following. The miniature is on the original recto. The very angular and regular littera textualis with versals touched in red, the fairly austere marginal decoration and the accomplished penwork probably suggest a monastic origin of the manuscript in question. On the verso, there are two grotesque heads with peculiar shields on the back of their heads emerging from the tips of the first versals in the top lines of both columns. As they are drawn in brown ink and touched in red, it seems likely that they were executed by the scribe rather than by the illuminator.

These two heads, the pen and wash style of the historiated initial, and also the decorative discs in red and green that are incorporated into the decoartive border bear some striking similarities to manuscripts from the Upper Rhine region, and particularly to some prayer books from central Switzerland that were made in the mid-fourteenth century. Susan Marti examined a couple of Prayerbooks from the Benedictine Abbey in Engelberg, Switzerland, that were made by members of the nunnery there (cf. Marti 2002). Although the decoration of these Prayerbooks is artistically on a different level than the present leaf, i.e. less accomplished regarding penwork, script and borders, they share some interesting parallels with this historiated initial and the concept of border decoration. Also, the colors in the Engelberg prayerbooks as well as in most fourteenth-century illuminated manuscripts from the Upper Rhine region, are much more intense and bright than those subdued hues on the present leaf (see e.g. Beer 1959 and Beer et al. 1997). However, the rather sketchy painting technique that sometimes resembles pen and wash drawings on paper seems to be common in both. For example, the plain diamond pattern in red lines on Mary's blanket to indicate cloth or drapery can be found in a similar way in the Nativity of the Engelberg prayerbook that is now kept in Manchester, John Rylands Library, where it is employed to decorate the Christchild’s white swaddling cloth. The contours in this manuscript are equally in red; something that is quite unusual elsewhere. Moreover, the Engelberg manuscripts have figurated and historiated golden initials that are decorated with black floral or geometrical ornaments, remotely comparable to the geometrical patterns that are imprinted onto the initial here. In addition, the marginal decoration of the Engelberg manuscripts abounds in small discs in red, gold and green with similar crosses or stars, which mainly occur at corners of pages or decorative bars. These parallels are certainly not sufficient to suggest that the present charming leaf was made in Engelberg or in Central Switzerland, but they do point to a monastic place of origin that was artistically linked to it.

Leaves from this region and from this period are exceptionally rare.

Literature

Ellen J. Beer, Beiträge zur oberrheinische Buchmalerei in der ersten Hälfte des 14. Jahrhunderts unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Initialornamentik, Basel and Stuttgart, 1959; Ellen J. Beer, Andreas Bram, Cordula Kessler, Buchmalerei im Bodenseeraum, 13. bis 16. Jahrhundert, Friedrichshafen, 1997; Susan Marti, Malen, Schreiben und Beten. Die spätmittelalterliche Handschriftenproduktion im Doppelkloster Engelberg, Zürich 2002.