The Spanish Forger Musician Harping for a Recumbent Queen

The Spanish Forger (active Paris, c. 1890s to 1930s?)

, c. 1900-1925(?)The Spanish Forger (active Paris, c. 1890s to 1930s?)

Description

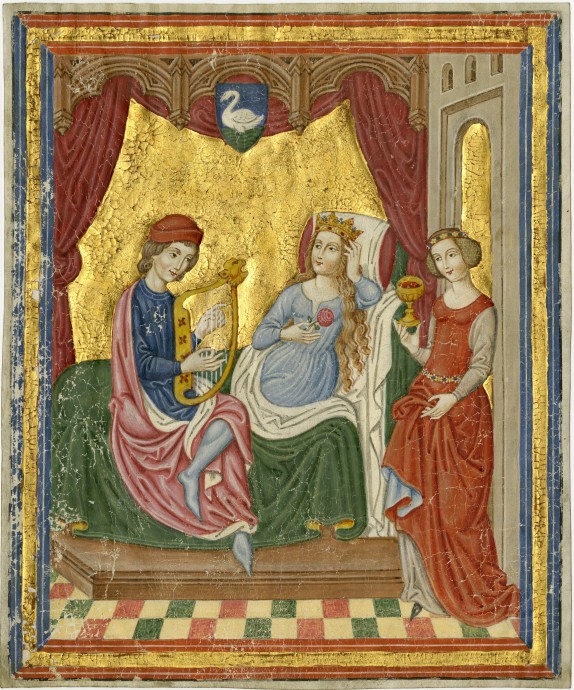

Exuding the Spanish Forger’s hallmark charm and fantasy, this miniature shows a courtly scene with a man playing a lion-headed harp. A crowned Queen reclines in a luxurious bed and listens attentively with a red rose held in her hand. Nearby, a maiden appears in doorway holding a chalice of wine. The scene is set in a curtained bedchamber with a wooden screen supporting an escutcheon with a white swan, all on a crackled gold ground and framed in borders of red and blue.

The subject must have appealed the Spanish Forger since it reappears in at least four other known leaves (figures 1 and 2; L14, L140, and L 235), with one variation showing a reclining nude woman (L85). Standing apart from these others, the present miniature adds a crown on the head of the reclining woman and a white swan above. The swan was the emblem of Claude de France (1499-1524), wife of Francis I, and was perhaps seized upon by the Forger to give the appearance of royal provenance. The desirability of this type of odalisque-inspired scene is perhaps tied to the uproar around Édouard Manet’s Olympia, exhibited in 1865 (see Voelkle 2018, no. 11).

Unmasked in 1930 by Belle da Costa Green, then director of the Pierpont Morgan Library, the Spanish Forger is known today as one of the most skillful, successful, and prolific forgers of all time. In 1978 a retrospective exhibition of was organized at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, revisited with an exhibition in 2014 at the Binghamton University Art Museum. The Forger was active already in the 1890s and was still painting in the 1920s. The Forger borrowed freely from chromolithographic editions published in Paris for compositions, especially the series by Paul Lacroix, which suggests the Forger may have been employed by one of the Parisian publishing houses. Remnants of old Parisian newspapers have also been found inside the frames.

Like others, the present miniature is painted on medieval parchment – a reused sheet from an unillustrated Choir Book – and typifies the Forger’s methods, including the use of a crackled gold ground. Scientific analyses of other works by the Spanish Forger has revealed the presence of green copper arsenite, a pigment not available before 1814. Apart from minor flaking of the gold and the expected signs of age in the borders, more apparent at the left edge, the miniature is in good condition, with a carved and gilded sixteenth-century Italian frame.

Provenance:

Private Swiss collection

Literature:

The present leaf is recorded in the ongoing inventory of works by the Spanish Forger as L285. For others and on the Spanish Forger’s other works, see:

W. Voelkle and R. Wieck, The Spanish Forger, New York, 1978, no. L14, fig. 225.

S. Hindman, M. Camille, N. Rowe, and R. Watson, Manuscript Illumination in the Modern Age: Recovery and Reconstruction, Evanston, 2001.

W. Voelkle, “The Spanish Forger: Master of Manuscript Chicanery,” in The Revival of Medieval Illumination: Nineteenth-Century Belgium Manuscripts and Illuminations from a European Perspective, ed. T. Coomans and J. de Maeyer, Leuven, 2007.

W. Voelkle, Holy Hoaxes: A Beautiful Deception, 2018, no. 11 (L140).